Paul Vecchiali's Theater of Feeling

How Paul Vecchiali built his own grammar of care, fusing theatrical intimacy with radical tenderness.

Within moments of sitting down to watch Paul Vecchiali’s Rosa la rose, fille publique, a bittersweet melody swelled in my ears. It felt hauntingly familiar, yet before I could place it, it slipped away.

That rush of something beautiful arriving and vanishing all at once stayed with me. Vecchiali has a way of weaving your heart into frames that feel strangely intimate. Instead of announcing itself to you, Vecchiali’s cinema drifts into you like a half-remembered dream. And when the story ends, it stays.

What does it mean to stage life — and still arrive at something true? Vecchiali’s theatricality is the form through which his deep humanism emerges.

And that resonance? It’s worth holding on to.

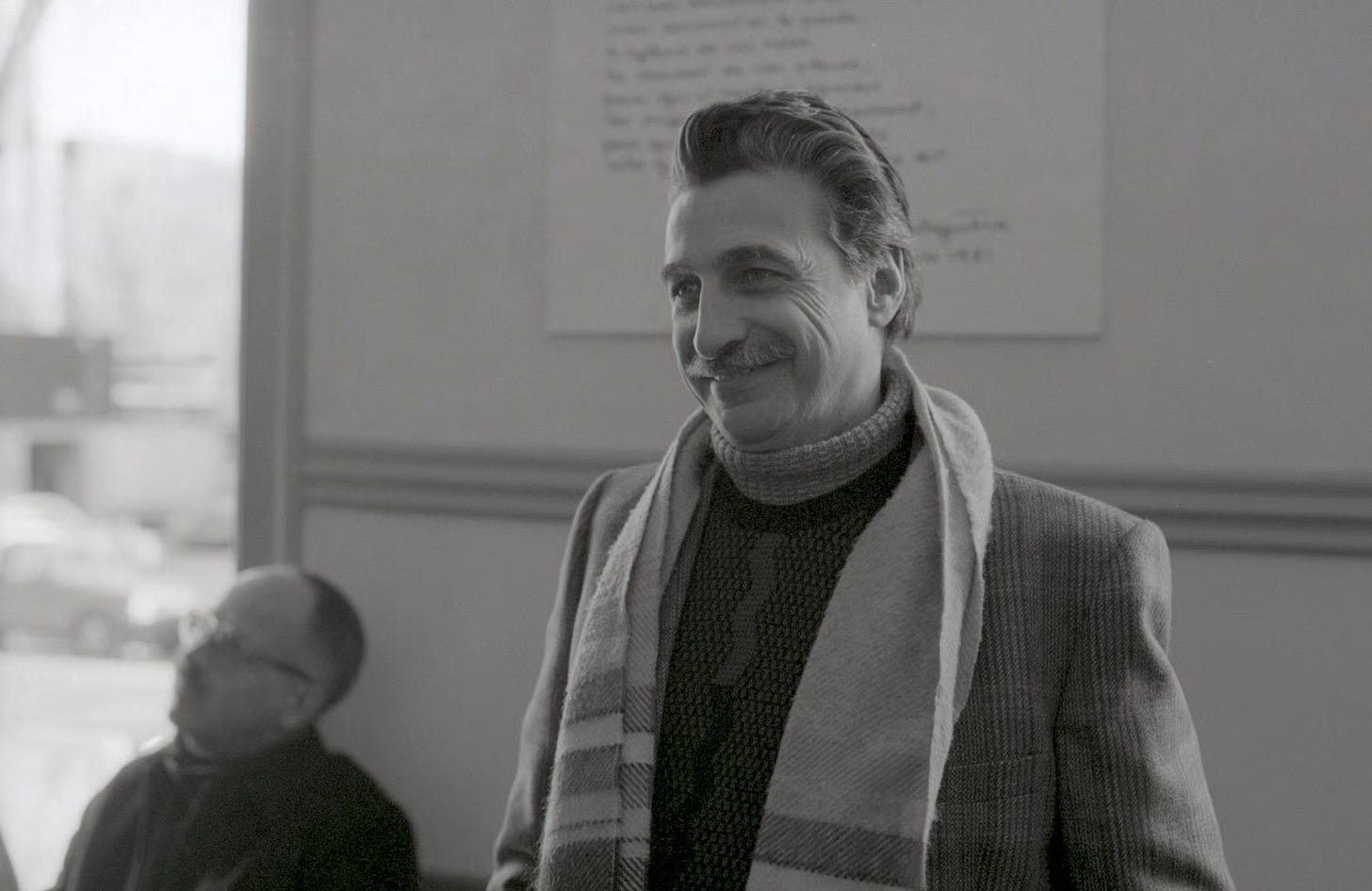

Paul Vecchiali, who passed away in January 2023 at the age of 92, never fit neatly into the story of French cinema — though he undeniably helped shape it from the margins. Born in Ajaccio in 1930, he grew up in Toulon and was enamored by film at a young age, watching Anatole Litvak’s Mayerling (1936) at age six and developing a crush on Danielle Darrieux.1 Throughout the 1940s, he continued to attend the cinema during the French occupation. Once he moved to Paris, he began studying at the École Polytechnique, but was called up for military service for the Algerian War. It was there that he subscribed to Cahiers du cinéma. “It was almost my only contact with the outside world,” he recalled to Libération in 2015, reflecting that when Jean-Luc Godard later asked him why he went to war as an anarchist, he told him, “I felt capable of being responsible, in accordance with my convictions, and if I hadn't gone, they would have enlisted another guy in my place, and I don't know what he would have done.”

This sense of responsibility — a refusal to look away when others might — became the cornerstone of his cinema, where he gave voice to those so often left unheard.

Upon returning to France, Vecchiali rushed to watch Godard’s Breathless and Jacques Demy’s Lola. These experiences, according to him, were the tipping point for his own foray into cinema. In 1961, Vecchiali made Les Petits Drames. “I edited my first film alone, in the living room of Nicole Courcel and Michel Piccoli, who were acting in it and living together at the time,” he told Libération. As a final grace note, his beloved Darrieux (a Max Ophüls favorite) had her own cameo. Devastatingly, the film was destroyed in a fire, though he would work with Darrieux again for At the Top of the Stairs in 1983.

Short films were next for Vecchiali, as was criticism. Éric Rohmer, who was editor-in-chief of Cahiers du cinéma from 1957 to 1963, received a letter from Vecchiali, who wrote that the magazine had published “a mistake about a film by Chabrol and one by Fuller.” While Rohmer wrote back that Vecchiali was, indeed, right, the letter remained in his office even after his dismissal — until Jacques Rivette took over and noticed it. From there, he invited Vecchiali into the fold, asking him to write about Sam Peckinpah’s Ride the High Country. “Criticism was essential to me, to keep in touch with cinema when I was beginning to make it,” he recalled to Libération. “It is very important for me to remain whole, filmmaker and cinephile.” In the Radiance Films release of Rosa la rose, critic David Jenkins shares that Vecchiali’s most beloved review was on The Umbrellas of Cherbourg by Demy, an auteur who undeniably inspired Vecchiali and, eventually, became his closest friend.

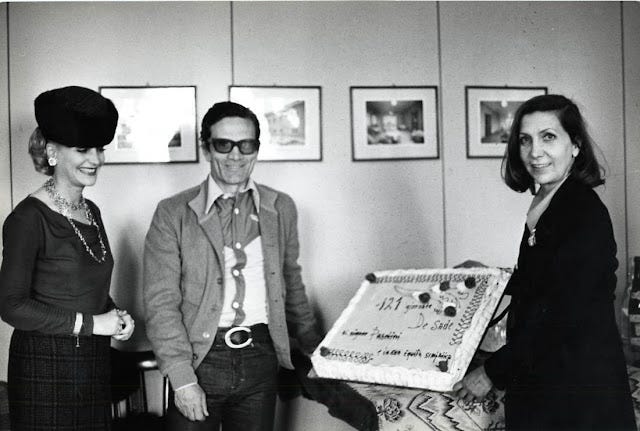

Vecchiali's friendship with Demy rippled outward, inspiring others as well. At the 1974 Venice Film Festival, Pier Paolo Pasolini (who was in the pre-production stage of Salò) saw Vecchiali's greatest critical success, Femmes femmes. He raved, dubbing it a “ménage à trois of reality, cinema, and theater.”2 He then proceeded to cast its two leads, Hélène Surgère and Sonia Saviange (also Vecchiali’s sister), in his controversial landmark film. We also have Vecchiali to thank for the now-beloved casting of Catherine Deneuve and Françoise Dorléac in Demy’s The Young Girls of Rochefort. As he explained to Libération, Demy initially aimed to have Brigitte Bardot and Audrey Hepburn. Vecchiali retorted, “What a pain, take the Dorléac sisters!”

Two years after the premiere of Femmes femmes in Venice, Vecchiali founded his own production company, Diagonale. It was less a business venture than a quiet revolution; a way to bypass the rigid, male-dominated systems of French cinema in the 1970s and create a sanctuary for himself and his peers. Funded largely through his own resources, Diagonale became a refuge for filmmakers with no interest in conforming. Jean-Claude Biette, Marie-Claude Treilhou, and Jean-Claude Guiguet all found support there, and Vecchiali even served as a producer on Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. The goal was simple: make the films they wanted to make.

The stories born under Diagonale shared an ethos of lived experience. Communities bloom on screen, existing with total authenticity. The films carried queer currents without needing to declare themselves queer films; they also gave space to other taboo lives (sex workers, the sick, the poor), revealing people in all their contradictions and ambiguities.

To sustain this freedom, Vecchiali worked tirelessly in television. “I did everything: TF1, France 2, France 3, La Sept… They came looking for me because people knew I worked fast, and I needed to make money because I hardly paid myself on the films produced by Diagonale,” he told Libération. Between this steady work, his own financing, and government support, the system held for decades. And while it never brought him the international recognition he deserved, he found peace in his independence. “I made my films at home with my own money, and I didn’t owe anything to anyone, I was calm,” Vecchiali recalled to Caimán Cuadernos de Cine in 2015.

Even with Diagonale’s vitality, Vecchiali remained at odds with the broader industry. His refusal to conform kept him on the fringes. But it’s also there where he found his freedom. “The margins are a liberation because society is obnoxious. I prefer it kind, but it’s obnoxious,” he remarked in 2015. Luckily, a few insiders quietly took note. Rohmer, fascinated by this underground counterculture, kept tabs on Diagonale and quietly encouraged C’est la vie! in the 1980s, even as other Cahiers critics tore it apart. Vecchiali’s cinema lived in this tension: outside the establishment, yet no less important to the story of French film.

If Diagonale gave Vecchiali freedom, his grammar came from elsewhere: his cinephile past. The Ophülsian glide, Renoir’s open frame, and a 1930s humanism make room for an entire ecosystem of lives. Vecchiali composes with bodies the way those earlier masters did, so blocking becomes intimacy, and the long take gives feeling time to arrive.

For Vecchiali, theatricality went past mere performance. To stage something is to feel it with a whole heart. “For me, in the theater, the feeling is in the legs … Feelings can be communicated by the legs, not by the head or by psychology,” he explained to Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. The stage is a score; the legs play it. In cinema, the frame is that stage — motion over motive, kinesis over psyche.

You can see that grammar from the first minutes of Rosa la rose: a gliding camera, a city scored by accordion, and long takes that let Rosa’s steps do the talking. Opening like a fairy tale lit by neon (almost Demy-tinted in its exuberance), the camera moves as if it's listening. Rosa’s agency registers first in motion: she floats through streets, claims space, then slows… as if the film were measuring the cost of desire in her very steps. The emotional cadence is something we feel before any sentiments are spoken. By the end of the film, as dawn breaks, the candy-colored spell we’ve been ensnared in has thinned. The lonely, empty streets speak volumes. Heartbreak arrives without announcing itself.

The way Vecchiali adapts his cinematic language by genre is exhilarating. If Rosa floats, The Strangler measures, turning movement into ritual. The thriller opens with a hyper-stylized killing, before scrapbook credits announce Vecchiali’s playful hand — even in grisly territory. What might be sensational elsewhere becomes staged and ceremonial: tempo, distance, and touch do the work, while the recurring white scarf functions less as a prop than a ritual object. “I spent fifteen nights walking around the suburbs of Paris in a receptive state,” he recalled to Caimán Cuadernos de Cine, noting that The Strangler “was more like a poem about the night.”

Émile (Jacques Perrin) is not a stereotypical pulp monster. He knits scarves, lives under his grandmother’s photo, while The Little Prince sits by his bed like a relic of broken innocence. The camera moves as if it were a patient dance partner, holding where it needs to. Early on, a bar erupts into an almost-surreal, single-take chanson-style number, pivoting from violence into trance. As always, Vecchiali’s theatricality keeps the film from tipping into the macabre. And when authority stumbles, his usual chorus asserts itself. At one moment, sex workers band together to seize the petty thief they think is Émile, not for spectacle but for justice — as a community redrawing moral lines the police can’t hold. Tenderness meets terror, while compassion dances with compulsion.

When asked by Caimán Cuadernos de Cine if he considers passion a form of anarchy, Vecchiali replied, “Yes, let's say it's the rejection of everything around us for the benefit of one single being.” We have now come to 1988’s Encore, where that belief meets his “legs-first” credo and becomes a choreography of care. From the outset, the film declares itself a play: a camera circles the central couple in bed, then pans out so it feels as if they’re on a stage. After the first song, we hear applause. In the subway, “Stage right! Stage right!” is shouted as a stranger bangs on the window, turning the platform into a proscenium. Long takes become acts, while time passes offstage. It is not ours to witness.

Encore is often cited among the earliest French features to face AIDS directly, yet it refuses to become “issue cinema.” Small kindnesses, like money given to a homeless man, join Vecchiali’s ever-familiar chorus of the everyday. The film moves like a memory musical, singing love until the voice gives out. Vecchiali doesn’t psychologize what the body can stage.

Long before Rosa la rose, The Strangler, or Encore, Femmes femmes lays down a template for the grammar we’ve been tracing. A beautifully melancholic chamber drama, it keeps us mostly confined to one room, where friendship is staged as survival. Two aging actresses, Hélène and Sonia, share an apartment and a past they keep rehearsing. Lobby cards of iconic actresses haunt their walls, and in one perfect ritual, the two apply lipstick to each other at the same time, their faces completing one reflection. Vecchiali lets movement live in the blocking rather than speeches, and theatricality is never an ornament, but a way to cope. A love letter to actresses and faded dreams that refuse to die, their duet is one voice in a larger chorus: ensembles where community is never, ever backdrop but the meaning itself.

You can hear this chorus in Drugstore Romance, too. The age-gap affair between the mechanic and the pharmacist never blows up into a scandal; it plays out on the block. What begins as a private longing suddenly spills into the public. Suddenly, the street becomes a stage once more. We may get pockets of Sirkian melodrama, but Vecchiali always remembers to keep the scale human. The romance leads, and the chorus carries.

Vecchiali generously invites viewers into his frames and proceeds to let them live there. As he said of audiences in 2015, “The film is a way for people to communicate; you offer them a plot of land and they build their house.” Inside the fiction, his ensembles work the same way: he offers space; they fill it.

The essence of Vecchiali’s work is freedom. This is also why his stance on identity was so unboxed. “I don’t like the word gay or the word homosexual,” he told Komitid in 2016. “The word means nothing. You shouldn’t confuse the sexual act with love. I’ve had adventures with men and with women.” That resistance to labels also rhymes with his feminist lens, where agency comes first and tabooed lives are treated without panic.

An interesting film is like a river coming out of a mountain (the script), which goes to the sea (the viewer); the more vigorous it is, the more crap it carries. In short, we can talk about heterogeneity, it's more accurate. There are masterpieces full of impurities.”

- Paul Vecchiali (via Caimán Cuadernos de Cine)

If we dive into that sea, we surface in a shared dream. With humanity for oxygen, Vecchiali’s theatricality lets us breathe — and sing.

We began with a melody that slipped away before it could be named. Vecchiali’s cinema works like that, too: feeling carried by movement rather than explanation. Jacques Demy once described Lola as a “musical without music;” Vecchiali makes that sentiment entirely his own. His films hum with desire and gesture, creating music even when it isn’t there. They are theatrical without falseness, staged so we can feel with every fiber of our being. This is why his work needs to endure: Vecchiali’s theater of feeling is the stage on which we take up the chorus and carry the tune home, long after the curtain call.

Seeing as how I missed out on Vecchiali summer, this article is here to shame me into submission. :)

The detail, context, and love you poured into describing his cinema is so artful! Just beautifully written and full of great quotes (the one I connect with most is probably “The margins are a liberation because society is obnoxious.") Seriously, wonderful work as always.

Where do you suggest I start if I'm want to dip into a Vecchiali fall?

I’ve been looking forward to this piece, and it’s beautiful!

The comment about feeling lying in the legs… I’ll be thinking about that all day.