Try a Little Tenderness: Cinema of Softness

A collection of films that give you the space to be gentle with yourself.

Long romanticized, film remains an alluring form of escapism. It’s a cliché near and dear to the hearts of all cinephiles, but what about the films that do the opposite? The ones that invite presence: heart full, shoulders lowered, with no demands but to feel. Soft cinema, if you will — a balm for the tender-hearted. After a long season of holding it all in, after months of noise, urgency, and ambition… I decided to breathe out.

I’ve just returned from sumptuous culinary escapades abroad, and I’m noticing (ironically enough) an urgency to slow down. Time off has been nonexistent these past few years — I’ve been hyper-focused on my work, and with that came a subtle kind of numbing. Hard to describe, but easy to feel. I’ve always been soft, but when you’re constantly pivoting from one task, one work of art, to another, you encase that softness; its liquid state suffocates. Suddenly, you’re mechanical.

Time away let my softness finally burst. I cried often throughout the trip, sometimes simply from being overwhelmed by beauty. The movies I so often immerse myself in suddenly felt like they were coming to life. As the trip came to a close, I realized I want to adopt a more mindful approach to how I live. To allow myself to feel again, and to do so regularly.

Cinema has such a hold on us. As mentioned, it can be a wonderful way to bid adieu to the present and carve out your own little world, even for a few hours. But even more moving is when a film connects you to something tender, and in turn, gives you permission to be tender with yourself.

I invite you to think of a film you return to when life overwhelms you. The one that slows you down and leaves you with the emotional residue you’re looking to connect with, be it a quiet ache, a warm peace, or a moment of introspection.

To honor this new, intentional pace I aim to set for myself, I want to share with you five films that are helping me feel again. Instead of merely telling a story, they earn your attention by lingering. Cinematic ellipses. Cradles of reflection. Rocking you into gentle solitude. When they come to a close, the stillness they leave in your bones might just mutate into something unexpected: the sensation of being truly, vividly alive.

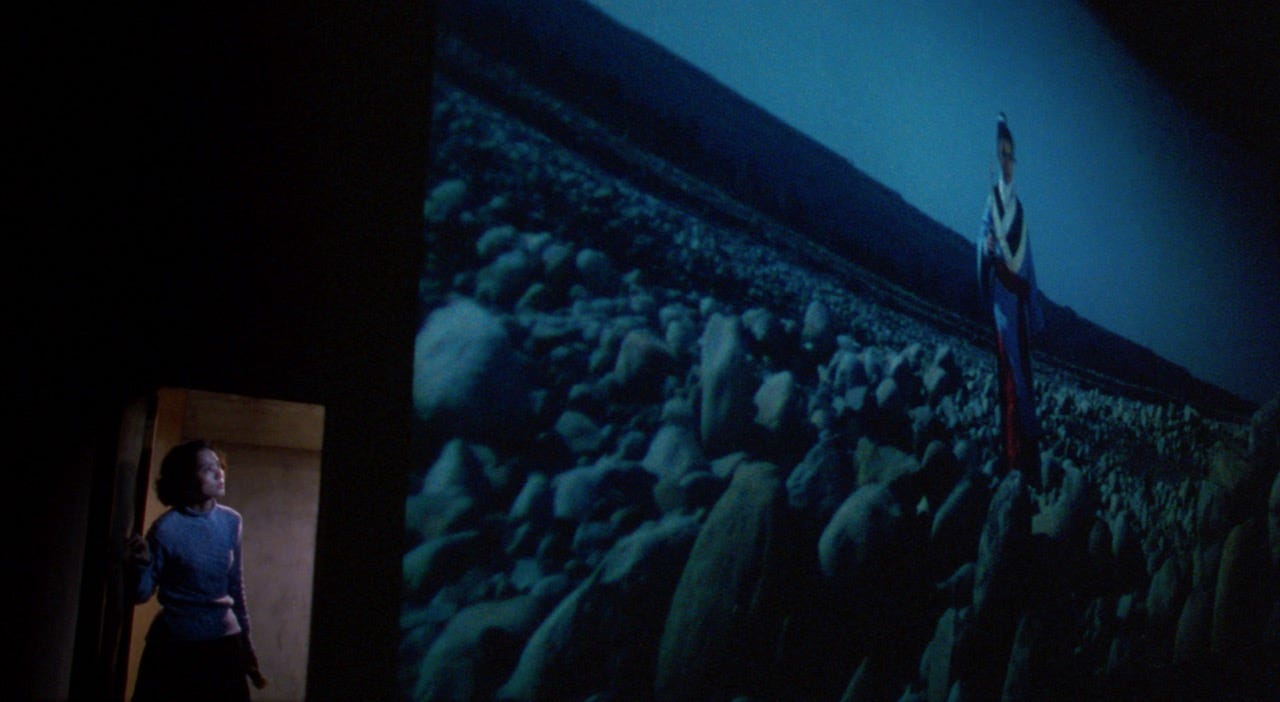

Maborosi (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 1995)

Memories may reside in the past, yet they can sometimes feel ever-present. Hirokazu Kore-eda’s debut feature lives in that space of unbearable stillness; it’s an exercise in restraint.

Shot almost entirely using natural light and with a delicate beauty to each scene, Maborosi follows Yumiko (Makiko Esumi), a young mother who suddenly has to continue on with her life after an unspeakable tragedy. Years pass, not a tear is shed. She moves on, finally, marrying and taking her now-toddler to live in a seaside village. Though her former life came to a sudden stop years prior, the memories — and the grief — linger.

From the empty halls to the distant staircases, so much of the film is built on absence. Cinematographer Masao Nakabori allows us to sit in that very absence. Slowly, as time passes, we see how trauma reshapes one’s rhythms. Yumiko’s new life is compassionate. It is patient. It is warm. But her grief doesn’t vanish, and she cannot return to the person she once was, loving without abandon.

Although her grief is a part of her now, we do get moments of reprieve. The way the light sweeps across the countryside, the way the children run and play, their reflections seen in the crisp water of a lake. Sometimes, those moments of peace may suddenly be interrupted, like when a bicycle bell echoes like a memory. Even in these moments of calm, the ghosts still drift by.

Some losses cannot explain themselves to you. The sadness that they bring cannot be cured, only carried. Maborosi understands this. There is no grand epiphany to this healing. Instead, much like the sea that Yumiko gazes at, it comes and brushes against you like a gentle tide, briefly grazing your sorrow before washing away once more.

Maborosi is currently streaming on Kanopy.

The Beaches of Agnès (Agnès Varda, 2008)

To step into one of Agnès Varda’s memoryscapes is to feel your chest loosen, swaddled in a blanket of warmth. The Beaches of Agnès, intended to be her final film, carries the weight of an auteur in her golden years, looking back not solely on her career, but also on the intimate moments that shaped her. For those who adore her work, it’s like reconnecting with an old friend — the kind you haven’t seen in ages, and when you finally do, you hold them tightly and never want to let go.

Calling The Beaches of Agnès an autobiography doesn’t quite capture it. It’s more of a collage, a drifting daydream. Old photographs, seaside reenactments, miniature sets, and snippets of Georges Brassens drift in and out, pulling you into her personal history as if it were your own. At one point, I could’ve sworn I smelled the sea.

There’s such generosity in how Varda shares her world. When she speaks of her great love, Jacques Demy, it’s impossible not to grieve with her. “As a filmmaker, my only option was to film him in extreme close-up: his skin, his eye, his hair like a landscape, his hands, his spots. I needed to do this, take these images of him, of his very matter. Jacques dying, but Jacques still alive,” she says, and suddenly, the act of filming becomes an act of preservation, of love, of holding on.

“I feel like cinema is the house I live in,” she tells us. The joy is that she leaves the door wide open, welcoming us in. I never want to go.

The Beaches of Agnès is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

The Fiancés (I Fidanzati, Ermanno Olmi, 1963)

Distance dulls some romances. But for others, it sharpens the ache of absence into something crystalline.

Ermanno Olmi captures that specific ache in The Fiancés and allows it to fester in quiet spaces. Giovanni (Carlo Cabrini), a Milanese factory worker, accepts a promotion that sends him to Sicily, far from his fiancée, Liliana (Anna Canzi). However, this isn’t immediately clear. The film opens in a dance hall, where two people who clearly share a connection spend their final moments together, yet remain emotionally miles apart. Once Giovanni departs, he initially seems swallowed by the stillness of his new life. Empty spaces in a foreign town engulf him as the factory incessantly hums. Every so often, his reality is interrupted as memories come, and that distance between himself and his beloved, which they once took for granted, begins to blur with longing.

Olmi’s style is quiet, elliptical. Flashbacks and present-day scenes dissolve into one another. But emotion (or rather, loneliness) pulses faintly beneath every frame. When the couple finally exchange letters, the floodgates of the heart open. Liliana writes, “That happiness frightened me,” and I shivered with acknowledgement.

Uncertainty lingers, too. Do we ever really know what ultimately happens? The Fiancés traps us in a liminal space of life’s redirection. The love between Giovanni and Liliana feels equally real as it does bittersweet. It becomes one of those loves we carry solely in memory – that relationship that never exactly failed; it just managed to slip away. Maybe that constant hum of machinery in the background isn’t just a symbol of modern progress. Maybe it’s the stand-in for love itself. Ever-present yet too often drowned out.

The Fiancés is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Goodbye, Dragon Inn (Tsai Ming-liang, 2003)

As rain pours outside, a cinema screens its final film. Inside, a few scattered patrons isolate themselves in empty rows, while others drift through the cavernous halls, almost as specters. Goodbye, Dragon Inn takes place over the course of one wet evening in a crumbling Taipei theater, as King Hu’s Dragon Inn (1967) flickers on its screen one last time.

I urge you to watch Hu’s wuxia staple before sitting down with Goodbye, Dragon Inn. While it’s not mandatory, I can assure you it’ll elevate your experience. Dragon Inn represents a cinema of the past, one that stands with a theatrical, almost mythic grandeur. Goodbye, on the other hand, offers a stark contrast with its quiet, reflective world.

Tsai’s film is an ode to the forgotten golden age of cinema, of movie-going, of the yearning for old establishments stuffed out by the glitzy and the new. To watch Goodbye, Dragon Inn is to sit with the loss of a communal ritual that once felt eternal. "People our age have the collective experience of moviegoing, but today the experience is different with DVD, satellite, etc," Tsai told Reverse Shot back in 2004. "You see these major changes over the past ten years, and it hits you the speed of things, how fast these changes are happening. But there's no way back. There's no use worrying or feeling sad about things."

Yet, as you watch the movie, it’s difficult not to feel pangs of encompassing sadness. A piece of slow cinema, as well, Goodbye gives you the space to mourn. Shot lengths linger agonizingly longer than we're accustomed to. However, if you let it lull you into an almost trance-like state, these heightened perceptions make room for emotions to take hold in your heart — a love letter to the memory of cinema.

“No one comes to the movies, and no one remembers us anymore.”

Goodbye, Dragon Inn is currently streaming on Kanopy or via rental on Apple TV.

Perfect Days (Wim Wenders, 2023)

Wrapping you in a tender current of stillness, Perfect Days allows you the time to breathe and sit with whatever’s stirring inside. I’ve reviewed this film to death, so I’ll keep it short: Koji Yakusho has the most expressive eyes, and Wim Wenders captures quiet beauty and resilience in life’s simplest rhythms. Sometimes, the way a song hits can shift your entire world.

“Now is now.”

Perfect Days is currently streaming on Crave (Canada) or is available to buy via The Criterion Collection.

Welcome back!

Thank you for this. I'm currently finding myself overwhelmed by activity after many years of chronic illness and my body is reinforcing that it's okay to slow down again. I've seen all of the films you mentioned except The Fiancés (which has been on my Criterion watchlist forever), so maybe today I'll give myself a little tenderness and finally screen it. :)

Hey, I’ve started an account where I collect some out of context captions of great films in cinema history. Just wanted to share it with the cinephiles around here : https://substack.com/@pariscinema?r=1x6h4r&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=profile