No One Wins This Game

Tracing the illusion of freedom from Radiance’s Wicked Games set through the wider cinema of Robert Hossein.

There is a particular kind of freedom that corrodes from within. It arrives with a jarring, pit-in-your-stomach recognition that the freedom you clung to may have been your undoing all along. Perhaps what we call “freedom” is only a more comfortable form of containment.

Robert Hossein’s cinema is built on this promise of autonomy — an obsession with moral blindness. His men move as if they are choosing, mistaking motion for agency, believing themselves above the system that encloses them. This sort of masculinity may appear stable from a distance, but up close, it’s posture. Hossein never allows that fantasy to hold. It is not motion but immobility, he would later suggest, that brings about a man’s fall. A man pacing inside a prison cell is in motion, sure — but he is not moving.

Across the three films in Radiance’s Wicked Games1 set — The Wicked Go to Hell, Nude in a White Car, and The Taste of Violence — Hossein stages variations of this very corrosion, moving from visible confinement to seductive delusion to violence stripped of ornament. The collapse is never explosive; it merely reveals what was already there.

What began as an exploration of his work gradually became something else: a way of returning to a cinematic world that became increasingly legible to me — one that understood how the very structures meant to secure us can become vehicles of erosion. It’s in this kind of acknowledgment that I was offered a strange form of solace, not because it resolves anything, but precisely because it refuses to.

Born in Paris in 1927 to a composer father and an actress mother, Hossein grew up between performance and composition, or, more accurately, between spectacle and structure. His father, André Hossein, would later score many of his films. The music lures you in at first, then returns in restrained, mournful rhythms that refuse to swell into release. As a child, Hossein described himself as silent, watching from a height, observing people below “like puppets.” In a 2007 interview with Vremya Novostei, he recalled climbing trees and looking down onto the street — “a theater that belonged only to me.” That detached, elevated vantage point never quite leaves his cinema.

After those tree-top years, Hossein formally trained under René Simon before performing at the Grand Guignol — the famously macabre theater once housed in a convent chapel. This again leaves Hossein straddling two opposites: discipline and artifice. The violence on stage was elaborate, yes, but it was choreographed. Shock has rules, too.

Even as he began directing for the stage, Hossein moved through French cinematic circles as an actor, often embodying roles marked by masculine assurance and composure. In 1955, though, the performance that truly put him on the map was Rémi Grutter in Jules Dassin’s now-legendary heist classic, Rififi. Rémi, a heroin addict embedded within his brother’s criminal machine, stands in stark contrast to the precision of Tony’s (Jean Servais) crew. In a film obsessed with time, codes, and professional restraint, he is a weak seam. His addiction keeps him circling and reactive. In motion, he is still stuck.

A decade later, in Bernard Borderie’s lush period romance Angélique (1964), Hossein embodies a very different register of masculinity. As Jeoffrey de Peyrac, the brilliant and controlled count, his composure is also his virtue, preferring intellect to force. Yet his belief that dignity will protect him leaves him exposed. The court does not respond to reason; instead, it responds with ritualized punishment.

On the opposite side of that illusion was Hossein’s role in Georges Lautner’s 1981 action-thriller The Professional2. As the unflappable Commissioner Rosen, he steps into authority stripped of romance. Rosen moves as an extension of the institution itself — not passionate, not theatrical, simply… procedural. If Jeoffrey believes dignity will protect him, Rosen behaves as though protection is irrelevant. His function is enforcement.

These performances reveal something consistent across decades. Whether volatile, dignified, or bureaucratic, Hossein’s men move through systems that promise order while making collapse inevitable. They inhabit roles that appear autonomous — criminal, nobleman, commissioner — yet each role narrows rather than frees. When Hossein begins directing for the screen, the emphasis shifts: he stops merely inhabiting these systems and starts designing them.

So, now that he is no longer solely inside the machine, what kind of worlds does he build?

The first world he builds is a prison — but not the one that ultimately traps his men. With his 1955 feature directorial debut, The Wicked Go to Hell, Hossein constructs a space where confinement is strangely coherent. The film divides itself cleanly into two: the prison and what comes after. It opens from above, with prisoners aligned in near-perfect symmetry. The frame is already imposing order before the narrative does.

It is telling where Hossein chooses to place any warmth. Behind bars, a strange communal rhythm forms, where levity becomes a means of survival. The musical interludes in which prisoners sing through cell doors suggest that confinement, however brutal, produces camaraderie. Our two leads, Macquart (Henri Vidal) and Rudel (Serge Reggiani), despise each other. At least the hatred is sustainable on the inside. Hierarchy clarifies roles, while proximity enforces a code.

Once they’re outside, though, the rules evaporate and the warmth drains almost imperceptibly. Meals are eaten in silence at gunpoint; a man collapses slowly against a wall, and the bond between our men begins to rot. When Eva (Marina Vlady) enters this fragile equilibrium, the suffocation intensifies. She isn’t the “cause” of their collapse — she’s a catalyst, revealing how little substance their loyalty ever had once the walls disappeared.

In his autobiography, La Nostalgie, Hossein describes learning early, through producers like Jules Borkon, that suggestion carries more force than repetition. While it can be easy to dismiss this “economy” as aesthetic minimalism, it’s actually a guiding principle. In The Wicked Go to Hell, that restraint is moral architecture. What destroys these men is not conflict itself, but what remains when order is gone. Even the final image withholds catharsis. From afar, the men are simply absorbed.

If The Wicked Go to Hell exposes the false promise of freedom, the second entry in Radiance’s Wicked Games set, Nude in a White Car3, makes it seductive.

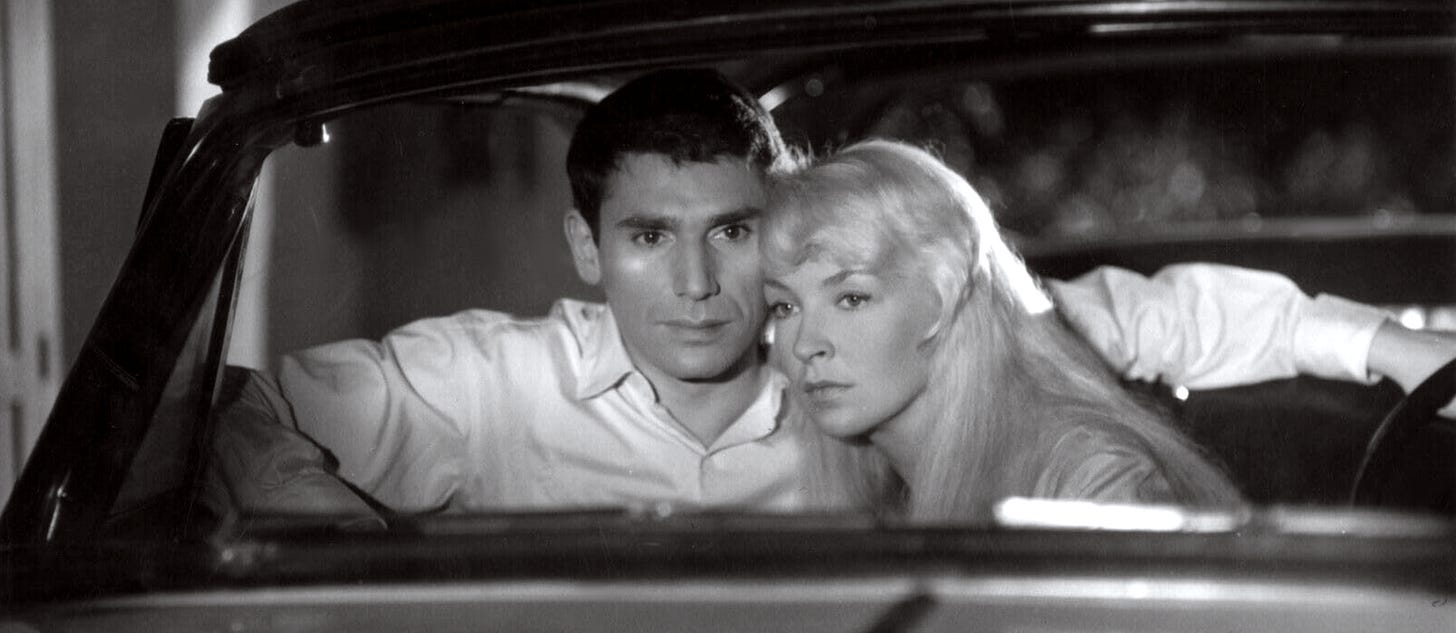

The 1958 film opens with the visual polar opposite of oppressive confinement. We’re graced with sultry jazz and an evening stroll along the beach. André Hossein sets a scene with a score that feels like a hand at the back of your neck, guiding you into the seduction before you’ve had time to object. As Pierre (Hossein) walks, a blonde pulls up beside him and invites him inside her car. Hossein stages the encounter with the same compositional control as the prison in Wicked, only now the architecture is desire. Pierre accepts her invitation without hesitation, and within moments, the woman parks, disrobes, and reclines in the driver’s seat. The camera slowly pulls back as she turns the volume up on the radio, and the brassy tune takes over. We never see her face.

That absence is the first warning. Pierre asks to see her, but she refuses, drawing a gun. He’s unceremoniously kicked out of the car, and the mystery woman tries to run him down. Rather than dwell on fear, Pierre is entranced. So much so, in fact, that he memorizes the license plate so he can track her down. For a man as self-assured as Pierre, it registers as a challenge, not a threat.

Like the men in The Wicked Go to Hell, Pierre mistakes motion for agency. While the former film charted the erosion of social bonds, the failure here is erotic. Shortly after, Pierre casually shrugs off his landlord’s eviction warning. His ease permeates all aspects of his life, confusing charm with control. He’s unbothered by consequence, which is precisely why he sees the blonde’s actions as flirtation.

Pierre tracks the car to a lavish villa. Instead of one blonde, he finds two: sisters, Eva and Hélène (Vlady and Odile Versois, real-life siblings). Once inside the villa, he enters another prison in Hossein’s world, constructed from doubling rather than walls. The flightier sister uses a wheelchair, while the other is her caretaker and always composed. In some scenes, both women wear their hair up; in others, both wear it down. An early split-diopter frame holds both women in sharp focus, forcing us, like Pierre, to search each face for confirmation. As jealousy, performance, and surveillance take over, we continuously ask: who is watching whom? Who is playing at innocence?

As Vlady explains in an interview on the Radiance disc extras, most of the film was shot in the villa, which undeniably enhances its claustrophobic atmosphere. The titular “nude” becomes less a woman than a surface for Pierre’s projection — desire morphing into suspicion, then paranoia. When he finally comes to a decision, the damage is done. He has already selected the version of reality that flatters him the most. In the interview on the Radiance disc, Vlady observes, “[Hossein’s] films are full of anguish.” For Nude in a White Car, that anguish is born from seduction itself — from the moment desire becomes a trap of one’s own making.

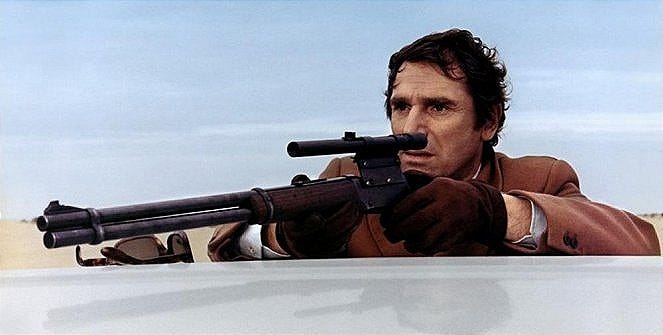

By the time we get to 1961’s The Taste of Violence (the third and final film in the Radiance set), Hossein no longer stages seduction or confinement. Now? He stages what comes after. The violence here is inescapable — administrative, even. An outlier in the set as the only Western, The Taste of Violence still manages to fit in beautifully, compressing rather than liberating.

Set in an unspecified Latin American country at the turn of the century, the film opens with revolutionaries aboard a train as they approach a tunnel. Fog consumes the screen, and once it lifts, bodies lie where some of the men rode. The others? They’re frozen in a tableau — like a memorial. Tellingly, André Hossein’s music is missing; mechanical sounds take over. There is no invitation into fantasy here. And when the music does make an appearance later? It’s slightly mismatched, as if the consolation has come too late.

The Taste of Violence follows a group of revolutionaries, Perez (Hossein), Chamaco (Mario Adorf), and Chico (Hans H. Neubert), after they’ve kidnapped the president’s daughter, Maria (Giovanna Ralli), in hopes of returning her in exchange for their imprisoned companions. As the journey unfolds through desolate landscapes, it becomes clear that this world is full of watching and waiting. Townspeople, soldiers, women at doorways, men on horseback, everyone frozen, forever witnessing the consequences of the actions of war, even when those actions are taken in the name of “freedom” — a word that shifts meaning depending on who speaks it. Perez, ostensibly our hero, seems deflated. He continues to fight, but he’s tired.

When it comes to moments of bloodshed, only what remains is shown. In one later scene, two bodies from opposing sides lie locked together in death, their hats thrown off next to them, while their arms are outstretched. Here, the symmetry replaces ideology. Once these men leave the land of the living, they’re indistinguishable. Immediately after, a similar image places Perez and Maria side by side, lying on the shoreline. This time, they’re both alive yet still barely separated. Right on cue, music plays, almost as a clue. The crooning lyric, “Hear me, destiny,” swells, suggesting that fate may be the story’s true antagonist. As Perez’s sister wisely says at one point, “No one wins this game.” It’s no accident that the men throughout the film are in white, while the women are in black, either. Grief is made permanent, while masculine pride keeps the machinery of violence in motion. In the final scene, two figures move slowly apart across the vast landscape. What they’re heading toward is neither victory nor conclusion. In Hossein’s cinema, motion is never escape.

Once Hossein directs 1970’s Falling Point, he has learned to operate by saying very little. Stripping the world down to its residue, he trusts that the corrosion no longer needs to be demonstrated. Gone are illusion and seduction, leaving only repetition — and the brief cruelty of discovering that pockets of warmth cannot alter fate.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that between these films sits Cemetery Without Crosses (1969), another Western similar to Taste of Violence, in which revenge coagulates into futility (it is his best-known directorial effort). Yet, a mere year later, what we witness are the skeletal remains of his argument. If the earlier films we highlighted staged prisons, villas, and revolutions, Falling Point reduces the world to a beach house, three masked men, and one girl. It may begin in a manner structurally similar to the second half of The Wicked Go to Hell, but nothing needs to be proven anymore.

Three masked men kidnap Catherine (Pascale Rivault) in hopes of receiving a ransom from her father. However, the youngest criminal, Vlad (Johnny Hallyday), compromises the plan by taking his mask off and allowing her to see him. Now, Vlad is told he must eliminate the girl. Can he follow through?

Falling Point fractures time itself, opening with flashbacks and then replaying the kidnapping from multiple angles. Later, a scream on tape is rewound and replayed over and over until guilt itself becomes a form of torture. Where The Wicked Go to Hell built tension through social collapse and Taste of Violence through ideological inevitability, Falling Point does so through circularity. The past, in Hossein’s cinema, never stays put.

What unsettles most is that Hossein allows tenderness to surface. It’s almost cruel by design. Vlad cannot kill Catherine in her sleep. He cannot do it outside, either. They find themselves sharing a sandwich. A beer can explodes as he tries to open it. For a fleeting second… they laugh. This marks the film’s most human moment — and its most merciless. It changes nothing. The moral suffocation remains, though now it has settled into resignation. What once erupted now simply concludes.

Working through Hossein’s films, one thing remains clear: he does not offer redemption. We don’t see his worlds detonate in spectacle, nor does he dignify collapse with transcendence. What’s most devastating is simpler than that. He exposes the illusion of freedom.

No matter where his men reside, the pattern remains intact. While they believe they are moving towards something, be it freedom, control, vengeance, or rescue, what they’re actually moving toward is the unraveling already underway.

In this way, Hossein’s cinema resists consolation. For those of us who do not feel reconciled, who have watched promises curdle into depletion, that resistance does something unexpected. His refusal to console sharpens our instinct: to interrogate what we want, what it costs, what is sold as normal, and what we no longer consent to.

And perhaps that is the strange solace: recognition itself.

Also known as Blonde in a White Car.