VIFF Dispatch #2: When the Edges Blur

No Other Choice, It Was Just an Accident, Nouvelle Vague, What Does That Nature Say to You, and Blue Heron

Three weeks after the Vancouver International Film Festival has come to a close, the twenty titles I saw are still swirling in the dark crevices of my mind. I always retreat into my own introspection post-festival season, allowing myself the space to soak up and trace what sticks and notice what fades — though I’m sure some of that is lofty thinking, when in reality, I’m allowing the sponge of my brain to be wrung out and placed to dry until it can begin to absorb more cinema.

I’m reaching that point now, where I’ve slowed my roll long enough that I miss the exploratory aspect of my passion. That’s good news for you, my friend, as it means more deep dives and essays are on the way very soon (along with more podcast episodes!) — I promise. But for now, let’s chat about five more titles I loved at VIFF.

For this second dispatch, I’ve selected films that find their characters teetering between control and chaos, myth and memory, or performance and collapse. When these edges blur, what we end up with is, miraculously, a glimpse of something true. Let’s begin.

No Other Choice (Park Chan-wook; South Korea)

Have you ever been stuck between desperation and derangement? There’s a fine line between the two. Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice, adapted from Donald E. Westlake’s The Ax (also tackled by Costa-Gavras in 2005), takes a corporate layoff and turns it into a living, breathing capitalist nightmare. A veteran of a paper mill (Lee Byung-hun’s Man-soo) is cut loose after decades of service, handed a ticking severance bomb, plus some eels for a “celebratory” barbecue. Determined to provide for his family, he vows to find work immediately — until he convinces himself he has “no other choice.” The plan curdles from there.

The film hit a personal nerve with me. In today’s job market, how could it not? Even people with no warning signs still worry, waiting for their own turn on the block. Yet this might be Park’s loosest-limbed outing: elegant rage colliding with slapstick panic. Kim Woo-hyung’s cinematography also alternates between play and precision. Frames crowd with tiny, nervy details; then the camera gets audacious, like planting us at the bottom of a glass as a drink is downed (unreal, by the way).

I loved the focus on Man-soo’s gardening passion. Gardening is an attempt to tame chaos (or, better yet, an effort to regain control). Man-soo tends leaves and trims stems while plotting his scheme: he’s “weeding out” whatever blocks his ideal life. You prune some things to let others flourish, right? The hobby seemingly flatters his self-image of being careful and gentle… until his actions expose a suppressed rot.

Color does a lot of narrative work here, as Park is fond of. Green trails Man-soo’s desire for stability (and resentment toward those still employed). Blue complements the green, particularly during familial moments, transforming the domestic into private isolation. Red needs no explanation, while purple mutates ambition into corruption.

The paper-mill metaphor is as relevant now as when Westlake published the original story. How maddening: Man-soo gives decades to a company that literally manufactures disposability. Paper is meant to be used and thrown away — just like him. “Pulp Man of the Year.” Let that sink in. It’s the working class in shorthand: extract labor → discard body. When Man-soo resorts to violence, he mirrors the industrial violence he once served. Meanwhile, the tender parts of his life sit within reach. The film juxtaposes gentleness with brutality, asking which one we choose when the rent is due.

Lee Byung-hun is excellent: he opens in cool composure, Man-soo’s confidence radiating through posture and voice. Soon after, Park nudges him into a Chaplinesque wobble, a slope he thinks he can climb and then barely clings to. You laugh and wince in the same breath, and Park lets air into the rage so you can breathe it.

The finale sees Park softly twist the knife. I cackled, then felt the aftertaste. No other choice but to laugh at the absurdity of the corporate hellscape, right?

It Was Just an Accident (Jafar Panahi; Iran/France/Luxembourg)

It Was Just an Accident begins with a road at night, and shortly after, the sound of a thud. The man driving has hit a dog. His wife consoles their daughter: “It was just an accident. Whatever will be, will be.” It’s a shrug (half prayer, half excuse) that sets the tone for Jafar Panahi’s moral labyrinth. Later in the film, another man drives down another dark road. This time, he slows down. He sees the dog. That small act of noticing stuck with me.

Vahid (Vahid Mobasseri) is a mechanic who suspects that a stranded motorist, Eghbal (Ebrahim Azizi), is the man who tortured him years earlier in prison. What follows isn’t quite the revenge thriller I expected; it is rooted much more in morality. When Vahid slows to avoid the animal, it mirrors that opening. From the Iranian cinema I’ve seen, animals often stand in for the moral conscience. Abbas Kiarostami (whom Panahi started his career assisting) also used them as silent witnesses to human indifference. Panahi inherits that here: the dog becomes a litmus test for empathy. When Vahid avoids hitting it (and note which part of the film this occurs), it’s a pivotal point. Maybe it’s humanity reasserting itself, even as vengeance threatens to consume him. Can that mercy extend to his own trauma? Should it?

A line in the film stayed with me: “The further you go, the more you sink.” You can apply that to these dark roads traveled, too. The farther the story travels, the murkier things get. Once we finally reach the end of the road, one marked by vengeance and memory, Panahi leaves us stranded. Nothing ever truly ends, and perhaps we’re left only with an echo of what we’ve done. The simmering rage this concluded on left me speechless.

Nouvelle Vague (Richard Linklater; France)

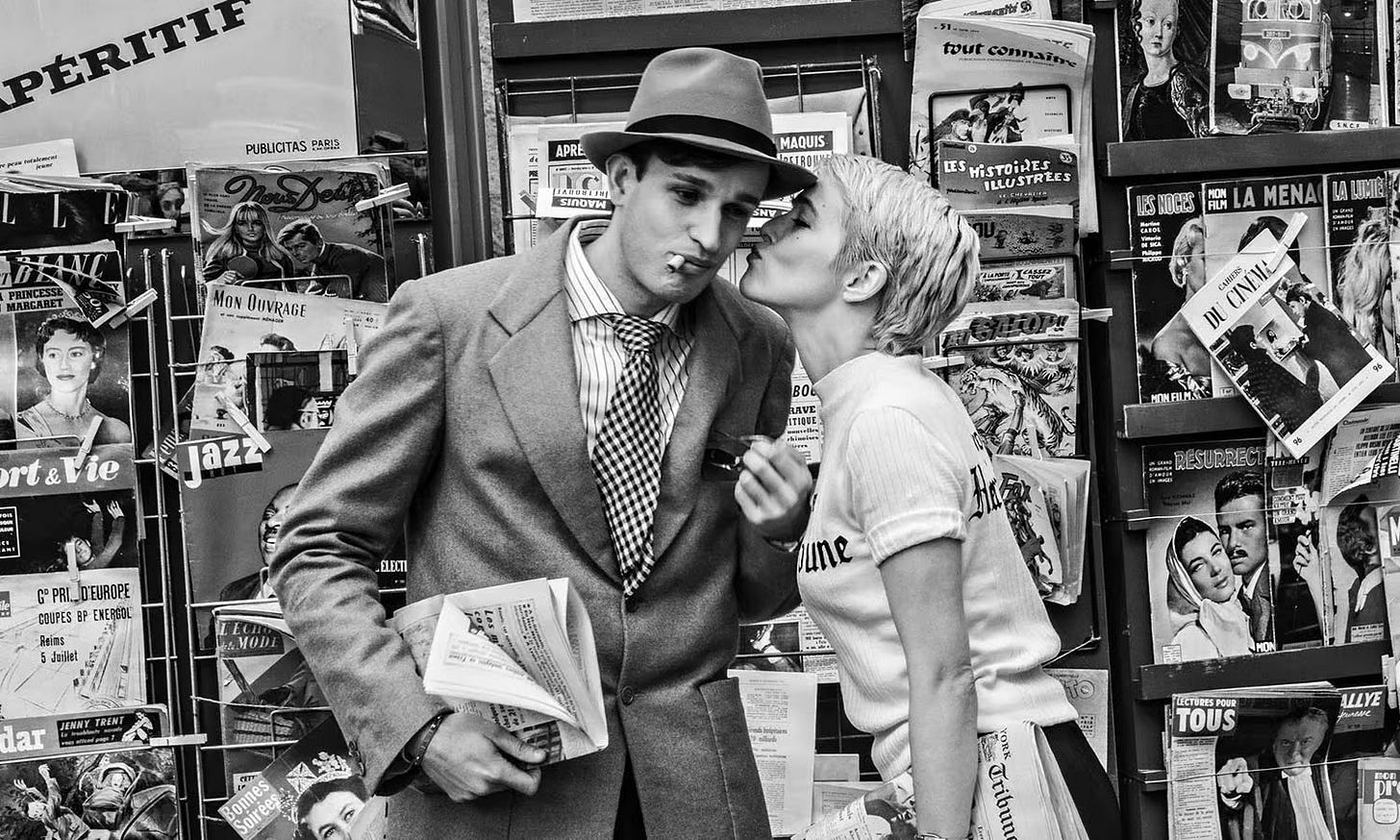

Richard Linklater has always been one of my favorite modern hangout artists, and Nouvelle Vague stays true to form: a breezy, cinephile’s bingo card of the French New Wave versus a solemn history lesson. Chronicling the making of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960), the film is full of playful winks: Guillaume Marbeck as Godard, Zoey Deutch as Jean Seberg, Aubry Dullin as Jean-Paul Belmondo, plus an entire array of legends brought to life: Truffaut, Chabrol, Rohmer, Varda, Demy, Rivette, Greco — all wandering into frame like old friends with uncanny resemblance.

Shot in 35mm black-and-white stock and in Academy aspect ratio (complete with cigarette burns, reel-change markers, and the faint crackle of a well-worn print), Nouvelle Vague so convincingly mimics the texture of 1960s French cinema that I sometimes forgot it was made in 2025, not 1959. When Godard sits down to watch The 400 Blows and we glimpse Antoine (Jean-Pierre Léaud) sprinting toward the shoreline, I had to stop myself from applauding. (Coincidentally, Truffaut’s semi-autobiographical debut was also one of the first films I ever saw alone in a theater — yay, solo cinema!). Linklater’s own adoration for the movement pulses through every frame; hardly surprising, given how much his own Before trilogy borrows from Rohmer (whose sly cameo sparked the theater’s loudest laughs). His enthusiasm is catnip; so palpable that my face hurt from grinning.

As Nouvelle Vague drifts from moment to moment, there’s joy in its conversational rhythms and in the thrill of seeing a revolution take shape. When a director’s passion hits this hard, it’s tough not to get swept along. Nouvelle Vague doesn’t rewrite history the way Breathless once did, but it still raises a glass to one of cinema’s most cherished beginnings.

What Does That Nature Say to You (Hong Sangsoo; South Korea)

A polite implosion, that’s what this was. Beneath the small talk and strained courtesies of meeting a partner’s family for the first time festers a familiar humiliation: the urge to prove your worth when you already suspect you don’t have any.

Thirtysomething poet Donghwa (Ha Seongguk) accompanies his girlfriend Junhee (Kang Soyi) to her family home, where an awkward afternoon with her father gradually morphs into an extended stay… complete with home-cooked meals, strained conversation, and too much soju.

What Does That Nature Say to You is as funny as it is excruciating, and by the time that one drink that probably shouldn’t have been poured is downed, the fallout feels as mortifying as it is inevitable. Hong Sangsoo’s deliberately blurry video aesthetic mirrors the emotional haze of his lead — a man collapsing under the weight of his own performance.

It’s a deceptively simple film that feels remarkably intimate, and I’m eager to revisit it when I’m not delirious on the final legs of a ten-day film festival (though maybe that was the ideal way to see it, who knows).

Blue Heron (Sophy Romvari; Canada/Hungary)

“I struggle now to remember much of my childhood. It only comes back to me in small fragments, and even those memories are hard to trust.”

What a way to start a film. Sophy Romvari’s Blue Heron pulls the curtain back to peer at those same fragile fragments: glimpses through doorways and windows, the sounds of cooking, the quiet moments that seem ordinary until you realize grief has been seeping through all along.

Set in the late 1990s, a Hungarian family moves to their new home on Vancouver Island, Canada. Sasha (Eyul Guven), age eight, settles in with her younger siblings, but it’s her eldest brother, Jeremy (Edik Beddoes), who struggles. Their parents attempt to steady an unraveling situation, while Sasha quietly takes it all in.

I loved how Romvari treats recollection as both fiction and documentary — the past reconstructed by an adult filmmaker trying to understand her younger self, or better yet, make sense of her memories. The scrape of a potato peeler at work. Oil crackling in a pan for a bit too long. The rhythmic thump on a wall. All tiny acts of resurrection. Blue Heron left me quiet, the way a childhood photograph does when you look at it too long.

What Does That Nature Say to You is perhaps Hong's most explosive work to date. You very rarely see something so loud in his films.