VIFF Dispatch #1: Heartbeats and Memories

Sentimental Value, Resurrection, Left-Handed Girl, Akashi, Kontinental ‘25, and A Useful Ghost

By the end of any festival, memory feels elastic and the brain turns to pudding. I’ve finally resurfaced after a month-long blur of pre-festival planning, red carpets, screenings, and beautiful exhaustion of the 44th Vancouver International Film Festival. There will be a couple more dispatches coming, but for this one, the connective tissue felt clear: the films I gravitated toward were all about continuity — of memory, family, labor, and creative or personal lineage.

Each one involves people clinging to meaning amid dislocation, finding ways to rebuild what’s been lost, or to keep moving even when the world forgets them. From Bi Gan’s century-spanning dreamscapes to Joachim Trier’s thorny family portrait, they all share a kind of communal heartbeat: people still trying to make sense of things, however fragile or foolish that effort may be.

Sentimental Value (Joachim Trier; Norway/France/Denmark/Germany/Sweden/UK)

What does “sentimental value” really mean? Usually, it’s shorthand for a knick-knack you can’t bring yourself to toss. But in Joachim Trier’s hands, it becomes something far weightier: a house swollen with memory, and the emotional baggage we take into adulthood.

Gorgeously shot on 35mm by Kasper Tuxen (The Worst Person in the World), the film feels lived-in from its first frame. The house itself becomes the central character — cracking under grief, humor, and what it resents most: silence. Both in the ways it lays bare the messiness of familial bonds (especially with such strained close-ups) and the dry, almost mischievous moments of humor, Sentimental Value often reminded me of Ingmar Bergman, whose work is very dear to Trier himself.

If Trier’s Oslo trilogy was stripped down and intimate, Sentimental Value is sprawling — each family member carrying their own textured backstory, yet never slipping into exposition (Stellan Skarsgård, Renate Reinsve, and Ibsdotter Lilleaas all had moments that almost broke me). It’s reflective in that signature Trier way, forcing you to sit with your own relationships and your own scars.

The film left me in a melancholy, contemplative state, but what surprised me most were the moments of levity. A surprise that, in the end, made it all feel so much more human. Even in our dysfunction, humor still exists. I started Sentimental Value musing about its title, which I often think of as just a phrase. By the end, it finally clicked: sentimental value is the weight of what we inherit, and the fumbling, fragile way we navigate healing.

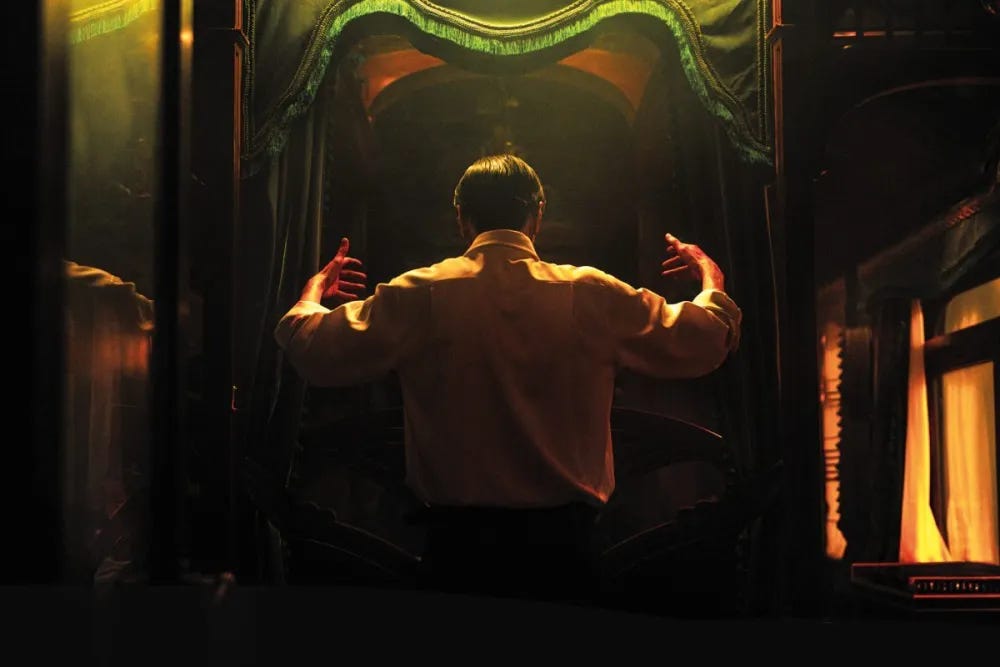

Resurrection (Bi Gan; China/France)

In Bi Gan’s Resurrection, the world no longer knows how to dream. Imagination has been traded for immortality. We’re introduced to the concept of “Fantasmers,” the only beings (or “monsters”) capable of dreaming and doing so on our behalf. Across a century, Bi crafts six chapters, allowing one fantasmer to wander through different incarnations — each echoing a different era of cinema (quite literally, his insides run a reel of film).

We glide through a silent film, a noir, past the grounds of a temple, to a station where a child learns to “smell” playing cards, and finally, into the rain-slick streets of New Year’s Eve, 1999. Throughout it all, Bi celebrates cinema, and the frame itself keeps changing shape and color, yet so fluidly it’s never jarring. The most dazzling segment comes the night before the new century: a glorious, 30-minute, red-soaked oner that carries us through narrow streets, into a karaoke bar (complete with a brawl), and back out to the docks and onto a boat. To sit in the dark and absorb it all? Electric.

Bi has said that all of the chapters are tied to the senses. What struck me is how he grounds all that phantasmagoria with small, edible anchors — such as a potato, an orange, an apple — appearing across eras. The Fantasmer takes and eats each, tethering himself to physical sensation. These foods become a language of touch and taste, a reminder that to eat is to remain human. A proof of continuity.

The best way to approach Resurrection is to simply feel it. “Screens are getting smaller and smaller, and I want to evoke that old feeling of watching films in theaters,” Bi told Variety. “Every director creates based on their own life experiences. This film is my emotional response to this land — a celebration of the lives of people who have shared this space with me over the past century.” Honestly? By the end, that feels true for us, too.

Left-Handed Girl (Shih-Ching Tsou; Taiwan/France/USA/UK)

Negotiations are at the core of Shih-Ching Tsou’s Left-Handed Girl, whether grappling with a sense of duty and freedom, or with tradition and modernity. Set in the bustle of Taipei’s night markets, the film follows a mother, Shu-Fen (Janel Tsai), and her two daughters, I-Ann and I-Jing (Ma Shih-yuan and Nina Yeh, respectively), as they relocate back to Taipei to open a noodle stand. Shu-Fen and her eldest daughter, I-Ann, are bound by generational tension and economic fragility, while five-year-old I-Jing is the scrappy observer, trying to navigate a world where the adults are too burdened to guide her.

Tsou has called the film a “love letter” to Taipei, and the result feels personal and alive. Left-Handed Girl runs on the city’s crowded tempo: neon tubes stutter over mopeds, stalls narrow into single-file corridors, and the odd banquet hall moonlights as a meeting room. It’s clear-eyed about circumstances but never turns cold. These are people who care for one another; they just don’t always have the space to show it. Generational gaps aren’t always kind, so love sometimes lands sideways. Tsou draws from people she knows and shared stories, and it shows; we understand these women’s choices, even when they’re rash.

Co-written and edited by longtime collaborator Sean Baker, the film carries a rhythm that feels instinctive — even reactive — as if the characters are chasing the city’s own pulse. Shot by Chen-Ko-chin and Kao Tzu-Hao, the camera often drops to I-Jing’s height, tracking our pint-sized pilferer through tight, shoulder-to-shoulder lanes. When she slips between stalls or cuts down a side street, we follow like we’re learning her shortcut map. Taipei can feel enormous, but to I-Jing it’s simply home.

Tsou’s empathy for her characters is what sticks with me the most. The title nods to a superstition, but Left-Handed Girl answers with tenderness. What emerges is a lesson in living with your crooked bits — your family, your city, yourself. Call it a love letter to Taipei… and to the left hand that keeps reaching anyway.

Akashi (Mayumi Yoshida; Canada)

The first thing Akashi does is relax you. A frame awash with color — the greens are impossibly green, the blues so vibrant — all while dreamy synth strings float you along. A young woman walks beside a man, and she hands him a photograph. “Before I forget… don’t give up.” It’s such a gentle beginning, so full of light, that the sudden cut to black-and-white feels like a door slamming shut.

Mayumi Yoshida’s feature debut moves between two worlds. Japan and Canada, past and present, color and grayscale. Kana (Yoshida) returns home to Tokyo after ten years abroad to attend her grandmother’s funeral. Grief awaits, of course, but so does the fragile awkwardness of being a guest in a place that once felt like everything. This is what makes Akashi both personal and universal. The teasing remarks from siblings, the polite but gnawing distance of old friends… they’re all reminders that time changes our shape of belonging, and ourselves, too.

Yoshida’s command of tone is sublime. She pivots from the melancholy weight of loss to humor so naturally, it comes as a welcome pivot precisely when you’re trying not to cry (though I still did — a lot). Through a flashback, we learn of a long-buried secret that’s steeped in both sorrow and resilience. With Kana, we grow to understand that love and loss are forever intertwined. It doesn’t always need to be resolved, but learning how to sit with it is what’s crucial.

When I spoke with Yoshida on the VIFF red carpet, she told me, “Home isn’t necessarily a place; it’s people sometimes.” That sentiment feels like the soul of Akashi. It’s a film about crossing oceans (literally and emotionally) and, more importantly, about forgiving the versions of ourselves that time has left behind.

Kontinental ‘25 (Radu Jude; Romania)

What a world we’re living in. Radu Jude plants his camera (or, in this case, iPhone) like a witness and just lets the satire unspool. Orsolya, a Hungarian bailiff in Romania, oversees an eviction that ends in tragedy, and then spends the rest of the film trying (and failing) to convince herself that “legally, I’m not guilty.”

At one point, Orsolya falls asleep to Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour — a perfect companion piece for a woman convincing herself that guilt is a legal technicality. Ulmer’s hero insists on innocence; Jude’s heroine rationalizes hers through bureaucracy. Both are trapped in their own narration.

Kontinental ‘25 is bleak and hysterical all at once. People offer sympathy, but Orsolya keeps retelling the same story. Jude’s static frames and bone-dry humor turn guilt into something larger; as the grief turns into repetition, it’s swallowed up by the numbness of modern life. Even the mechanical dinosaur park in the background feels like part of the joke: monuments to our ability to distract ourselves from moral collapse.

A Useful Ghost (Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke; Thailand/France/Singapore/Germany)

Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke’s feature debut begins as a deadpan ghost comedy: a woman dies, returns as a vacuum cleaner, and resumes her marriage. Once it hooks you, it morphs into something far more profound. The ghost story, of course, is a Trojan horse. Boonbunchachoke takes this absurd premise and threads a sociopolitical undercurrent, exploring themes of pollution, memory, and what gets erased by those in power.

Boonbunchachoke has cited Jacques Rivette as an inspiration, and you can sense that presence here, not in style, but in spirit. There’s a Rivettian rhythm to how memory loops, while the film is also attuned to repetition: of labor, of mourning, of all the quiet roles we’re expected to play until we vanish from sight. Impressively, Boonbunchachoke drifts between registers with ease, balancing both humor and devastation exactly when needed.

Ultimately, A Useful Ghost is a film about visibility — who gets remembered, and who gets swept into the margins. Dust is everywhere: on the ground, in the lungs, and thick in the air. The vacuum cleaner becomes both a tool for order and a mechanism of silence.

Strangely, for all its tonal shifts, the film works beautifully and remains gentle. In a world choking on air and forgetting its ghosts, A Useful Ghost remains grounded in both sorrow and solidarity. Grief can be absurd, love can look like labor, and memory — like dust — never really settles.

I’m dying to watch Sentimental Value 🙌