Physical Media Treasures: The Fall Haul

Through and Through, The Cat, Los Golfos, The Betrayal, & Adela Has Not Had Supper Yet.

With all of my film festival work finally wrapped up, it’s time to give my unwatched physical media stack a little bit of TLC. After living in a delicious fog of media overstimulation, I naturally turned to kung-fu cats, carnivorous plants, and samurai disillusionment to level me out. This collection of films reminds me why I keep chasing the next strange image.

In other news, it’s also high time I dust off the cobwebs on my podcast. I’ve been a bit bummed I haven’t given the R&R pod the love it deserves, so I’ve been spending my free moments thinking about the wonderful films I want to dive into — complete with a talented roster of industry friends and filmmakers I’m tapping to get on the mic.

More to come on that soon, but for now, let’s get weird and rewind, shall we?

Through and Through (Grzegorz Krolikiewicz; 1973)

A deeply upsetting film that leaves a sensory itch all over. Grzegorz Krolikiewicz plunges you into a disorienting headspace made of claustrophobic frames, jarring edits, and an oppressive, almost rhythmic sound design that refuses to let up.

Through and Through is based on the real-life 1933 Kraków murder case involving Jan and Maria Malisz, an impoverished couple whose intense love for one another became the centerpiece of a sensational trial. They planned to rob a mail carrier on pension day, but when it spiraled out of control, three people were left dead: the postman and the owners of the apartment they’d rented for the crime. Only the owner’s daughter survived. What shocked the public most wasn’t the brutality of the crime, but the romanticism of the courtroom: each spouse took full responsibility in hopes of saving the other. Although both were sentenced to death, Maria was ultimately pardoned — on the very day of her planned execution.

Krolikiewicz presents only fragments of these events before the courtroom scenes arrive, and with them, the film’s most extended use of dialogue. Until that point, Through and Through rejects any straightforward narrative, replacing it with a swirl of weaponized silence or layers of droning, relentless noise. Initially, Maya Deren’s spatial disorientation came to mind, yet her work moves like a dream, where Krolikiewicz’s film lurches like an abrasive nightmare. More fitting comparisons would be somewhere in the vein of a rawer Dušan Makavejev, or the suffocating symbolism of Wojciech Has.

Notably, what I found most impressive is how Through and Through avoids showing overt violence altogether. Thanks to Bogdan Dziworski’s nauseatingly intimate camera, the crime doesn’t need to be seen. Instead, it’s replaced through intrusive close-ups of the victims’ faces (and Jan’s own expression of terror). It’s overwhelming in its brutality, precisely because of what’s left out.

Emotionally, the film is full of contradictions. Tender and brutal, disheartened and furious. When the closing monologues in court finally arrive, they feel like the only form of grace Krolikiewicz allows. A catharsis, of sorts.

You can purchase Through and Through via Radiance Films here or MVD Shop here.

The Cat (Lam Nai-Choi; 1992)

As swan songs go, The Cat might be the strangest. Yet for Lam Nai-Choi, it’s also weirdly fitting. Best known for Riki-Oh and The Seventh Curse, Lam bows out with a sci-fi–horror–action mash-up that you can’t help but just have fun with. The film, based on the novel Old Cat (an installment of the Wisely series and Nai-Choi’s second Wisely adaptation), follows Wisely (Waise Lee Chi-Hung) as he joins forces with a trio of aliens — one of whom is, yes, the eponymous cat — to defeat a goopy, tentacle-thrashing parasite which also happens to possess human bodies.

Along the way, we’re treated to a generous buffet of visual excess: an animal-fu fight between a cat and dog, stop-motion and puppetry madness, levitation sequences, and face-melting gore. The practical effects are pure camp magic, and the phrase “They just don’t make ’em like this anymore” has never rung truer.

Beneath the janky pacing and delightfully awkward dialogue, there’s something genuinely heartfelt in the mix. Like everyone involved was reverting to their childhood selves and living out whatever glittery, deranged genre dreams they still had left in the tank. The tone is a beautiful soup of contradictions, and it somehow works because it refuses to settle.

The Cat wears its ’50s B-movie maximalism on its sleeve. It’s gooey and strangely charming in its earnest chaos. If you love House, The Thing, or, well, some of, if not THE best darned cat acting put to camera, this is the one. Let movies be fun and weird again.

You can preorder The Cat via 88 Films here or MVD Shop here.

Los Golfos (Carlos Saura; 1960)

Carlos Saura’s debut feature opens with a jolt: a blind newspaper vendor is robbed in broad daylight. The film then cuts to the brutal grace of a bullfight. Madrid, too, enters the frame, seen as a city from the periphery.

Shot with non-actors and a raw, neorealist aesthetic, Los Golfos follows the lives of working-class boys on the margins. They’re always on the move, swiping what they can, be it food, trinkets, fleeting pleasures, all in the name of staying afloat. Itching to climb the social ladder, the “delinquents” come up with a theory: if their friend, a novice matador, makes it big, he may be their ticket to masculine glory. Crushingly, the realization is that no matter how bravely you perform, you’re still trapped in the ring.

Los Golfos is, put simply, bleak. Veritably so. Even the sensual flashes, like dance clubs or bodies moving at the beach, are fleeting. As quickly as they appear, they vanish, eclipsed by systemic immobility and the limits of dreaming under authoritarian rule.

Ironically, Saura never intended this to be his first feature. He had previously tried to adapt two books in the 1950s, but Francoist censors rejected both. The strategy for getting a film through at the time was to make your message vague. Imply, but don’t name. Saura didn’t shy away, and Los Golfos speaks through absence: a film where everything unnamed carries the loudest weight.

The film almost didn’t make it past the censors. As the Radiance Films booklet explains, Los Golfos was trimmed by 10 minutes, with officials insisting that the boys’ plight be portrayed as personal and not in any way allude to Spanish youth at the time. Even then, they weren’t satisfied. Los Golfos debuted at Cannes in 1960, but wouldn’t reach broader audiences for two more years.

This new restoration restores three of the four censored scenes, making it the closest we’ve come to the version Saura initially sent to Cannes.

You can purchase Los Golfos via Radiance Films here.

The Betrayal (Tokuzō Tanaka; 1966)

The Betrayal begins as if it will be a familiar chanbara tale, but by the end, a hollow devastation takes over. In Tokuzō Tanaka’s film, we witness what happens when the very notion of honor corrodes under systemic decay. Loyalty is twisted into a tool of exploitation.

Takuma (Raizō Ichikawa, of the Shinobi films) is a samurai asked to take the fall for the murder of a member of a rival clan. This wasn’t just any murder, however; it was disgraceful — a strike from behind. Honorable to a fault and engaged to his clan leader’s daughter, Namie (Kaoru Yachigusa), Takuma agrees. The promise? After a year in exile, he may return when the dust settles. What unfolds is a merciless cycle of broken promises. Betrayal piles upon betrayal. Even early on, with the flicker of Namie’s eyes when her fiancé accepts, we see that fracture instantly. Love sacrificed for duty.

Formally, it’s absorbing to watch how the film mirrors Takuma’s collapse. Tanaka starts with destabilizing handheld camerawork before settling into rigid statics, suggesting a temporary return to order that will not hold. Once we get to those fixed shots, we’re also offered selective framing, where certain scenes crop out figures, like showcasing attackers only from the legs, or Takuma on the ground. We’re given a subjective, ground-level perspective of humiliation. Most fascinating, however, was witnessing the exile period come and go, as if it were an ellipsis. By denying Takuma any narrative redemption arc or sense of urgency, Tanaka insists on futility.

So, what are we left with? Disillusion. “A samurai’s word is meaningless,” spits Takuma through maniacal laughter at one point, marking the erosion of the bushidō code. Even the film’s spectacular final act (which I won’t detail — it’s best experienced) is loaded with bitter irony. We’re dazzled by edge-of-your-seat thrills… yet it rings hollow. As Takuma’s worn-down body keeps swinging, what does it matter what the outcome is? His spirit is already destroyed. In the words of one character: “In this world, the faithless win, and the faithful lose … it’s the way of the world.”

Adela Has Not Had Supper Yet (Oldřich Lipský; 1978)

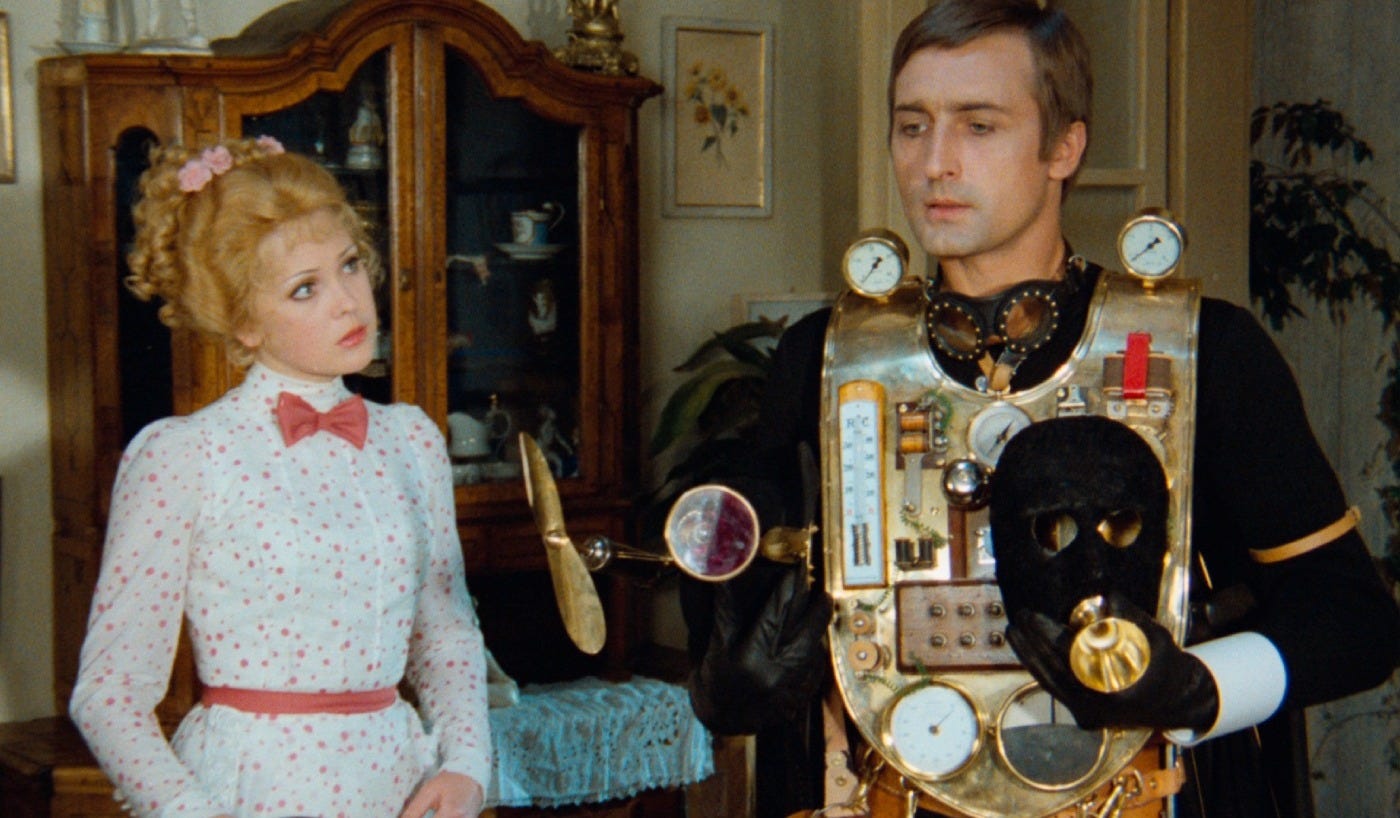

Adela Has Not Had Supper Yet may be in the running as one of my favorite detective spoofs next to Mario Bava’s Danger: Diabolik. Oldřich Lipský brings to the screen American sleuth Nick Carter (a dime-novel legend I admittedly didn’t know of!) as he’s summoned to Prague for a seemingly simple missing-dog case... only to find himself chasing an eccentric villain — mustache primed for twirling and all — who’s been feeding his victims to a carnivorous plant. Naturally.

Visual gags abound in Adela, and they’re played entirely straight-faced, which makes them even better. It plays like Peter Sellers–era Pink Panther by way of Inspector Gadget, with a flair for sepia tones, dime-novel illustrations, slapstick choreography, and sped-up chases. Carter’s (Michal Dočolomanský) crime-fighting arsenal is a delight, from retractable hat punches to bomb-sniffing spectacles, sprinkled with a healthy dash of steampunk swagger. What particularly surprised (and shocked) me was seeing that his partner, Commissar Ledvina, was played by Rudolf Hrušínský, whom I adored in Juraj Herz’s The Cremator. Almost unrecognizable, Hrušínský’s Ledvina exists primarily to fumble, eat sausages, and down beer — often at the same time.

The carnivorous plant, which lends its name to the eponymous title, is the real showstopper. Brought to moist, grotesque life by Czech surrealist Jan Švankmajer, Adela goes from weirdly charming to absolutely revolting, complete with a full set of teeth and a tongue. Gross.

I first tried watching this in the middle of film festival season, but I was too exhausted, so I circled back. If you’re even slightly soup-brained from too many meaty watches, this is a perfect reset button. There’s a gag in every scene, and beneath the spoof, Lipský still manages to sneak in a satire of bureaucracy and genre tropes. Overall, though, it’s a film that delights in being ridiculous — and a goddamn treat, at that. Supper is served.

You can purchase Adela Has Not Had Supper Yet via Deaf Crocodile here (the delux limited edition) or standard edition here.

Of all the titles listed, only Through and Through was on my radar, so thanks for the new discoveries! I'm probably most interested in Los Golfos and The Betrayal. Also, good on you for providing links in order to spread the physical media word. You should do more of these in the future :)