July’s Physical Media Treasures

My film-watching journey this July spanned emotional extremes, mainly through my physical media collection (many of which are new restorations!). The five films highlighted here offer a rich cross-section of cinema from around the globe, each reflecting a unique directorial vision marked by distinctive aesthetics, provocative ideas, and compelling narratives.

I'll say it right now: Paul Vecchiali has easily become my favorite discovery of the year, starting with the mesmerizing Rosa la Rose, fille publique — what an introduction. I'm already diving headfirst into Vecchiali's filmography, and a dedicated essay on his work is soon to follow; I look forward to sharing it with you when the time is right.

For now, please enjoy this lovingly curated list. I hope at least one of these gems intrigues you enough to spark your own cinematic adventures.

— M

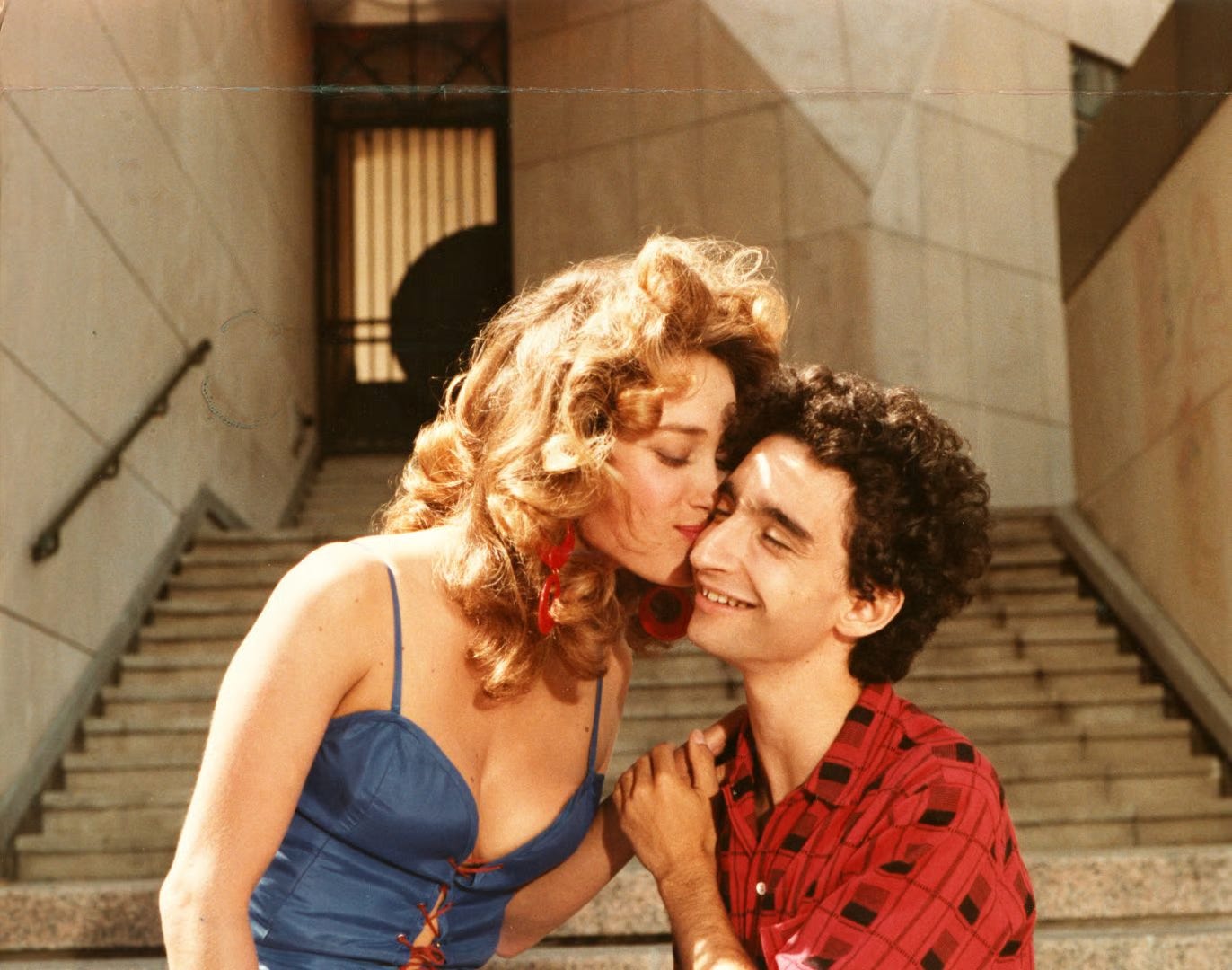

Rosa la rose, fille publique (Paul Vecchiali, 1987)

Radiance strikes again, and I’m left giddy to enter into Paul Vecchiali’s world, beginning with 1987’s Rosa la rose, fille publique. Opening with an alluring array of reds, pinks, and blues, Rosa instantly enchants, setting the stage as a fairy tale lit by neon, with gliding camerawork and music so tender. Jacques Demy’s visual enchantment immediately comes to mind, but Vecchiali’s fable trades whimsy for something more lived-in and tragic. Here, this pastel dream is grounded in the streets of Les Halles.

Marianne Basler (who received a César nomination for the role) is captivating as Rosa, a sex worker adored by her community who practically levitates through the camera with her charm. There’s a playful buoyancy to Basler’s performance, but don’t be fooled — the film never loses sight of her agency. Initially, she’s seemingly in control. She flirts, she works, she commands with her presence. As the story unfolds, however, we begin to sense the irrevocable ache she carries within her. Vecchiali doesn’t moralize, nor does he pity; instead, he places our heroine in the gnawing tension between desire and survival.

Vecchiali, who may have slipped under the radar compared to his Cahiers du cinéma contemporaries, is nonetheless an important figure in French cinema; for instance, he helped produce Chantal Akerman’s now-iconic Jeanne Dielman and later became the first French director to openly tackle AIDS onscreen. Diagonale, his production company, became a platform for championing queer narratives. First and foremost, however, he was a passionate lover of the craft he practiced, having become enamoured with cinephilia as a child. Watching Rosa la Rose feels, at times, like a blend of Demy and Rivette, with a sprinkle of Fellini (à la the colorful, carnival-esque band circling our lead’s orbit). Both theatrical and intimate, we drift down city blocks via long takes as your eyes dart around. In this world, every character has a voice, no matter how small, whether it’s a passerby on the street or the silent faces gathered around a long dinner table, frozen in a near-static tableau.

Eventually, the romantic spell begins to crack. Rosa’s comfort comes at the cost of authority. Pleasure is tethered to a slow erosion of autonomy. As the morning light creeps in through quiet Parisian streets, our fairy tale fades away, with only the lingering trace of heartache left behind. That final devastation: the realization that life rarely plays out like the movies, and that passion, more often than not, exists as a fleeting burst of joy within a world designed to wear us down.

You can buy Rosa la Rose via Radiance Films.

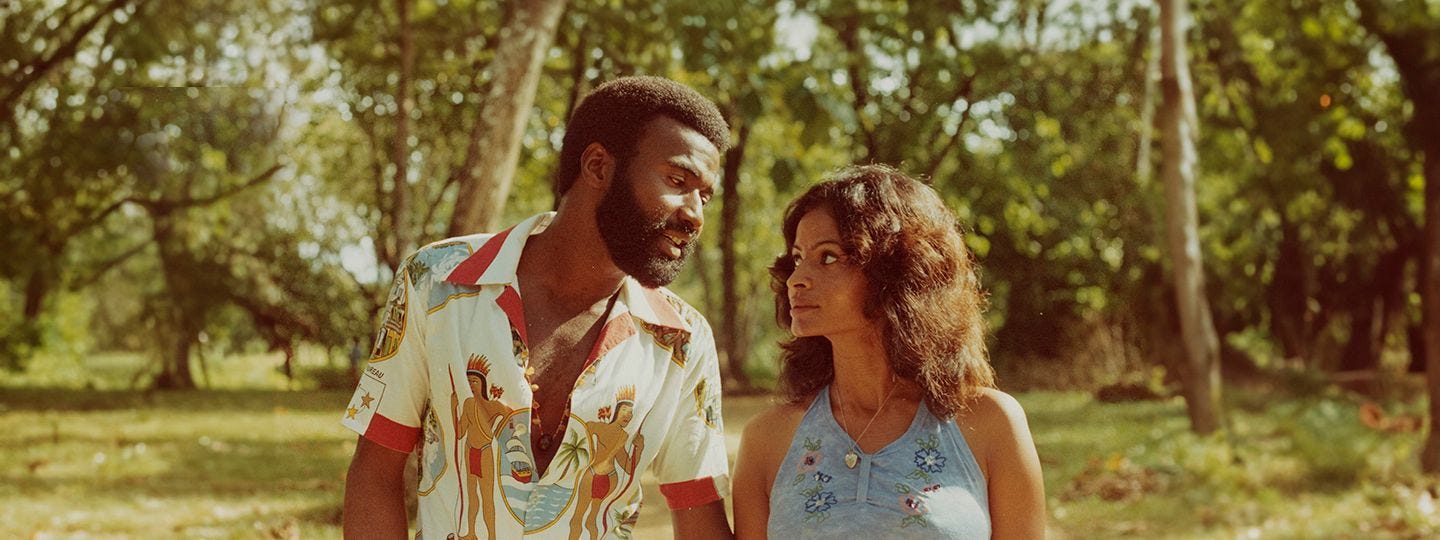

Wan Pipel (Pim de la Parra, 1976)

Made just after Suriname gained independence in 1975, Wan Pipel (which translates to One People) opens with a simple yet powerful text crawl that lays out Suriname’s layered colonial history: centuries under Dutch rule, followed by waves of migration from India, Indonesia, and China. That blending of cultures (and the beauty and tension of it) forms the beating heart of Wan Pipel. Yet, for a film often spoken of in political terms, it’s also deeply personal. Director Pim de la Parra poured everything into this project: his finances (which bankrupted him) and his marriage (which dissolved during production). To top it off, it took decades for the Netherlands to embrace the film with the respect it deserved.

The story centers on Roy, a Surinamese man who returns home from the Netherlands following his mother’s passing. It begins as a homecoming for him, but then slowly evolves into a journey of self-discovery and a reckoning with identity and belonging, all while navigating the cultural fractures of a newly independent nation. Roy himself is a complicated character. At times selfish and cruel, he’s hard to root for. Where Roy succeeds (despite himself) is as a lens into the complex patchwork of Surinamese life. His romance with Rubia, a nurse from a conservative Hindu family, runs parallel to his relationship with Karina, his Dutch girlfriend. There’s a clear metaphor at play here: Karina represents the lingering hold of the Netherlands, while Rubia embodies a reclamation of self and home. Wan Pipel may seem heavy-handed at times with its obvious metaphor, but it also resists a “neat” answer. It recognizes that identity is complex, especially when it is divided between languages, histories, and expectations.

While the pacing can feel loose, the experience of simply sitting with Suriname — its gatherings, street markets, music, and dance halls — transforms that looseness into something purposeful. It kept me engaged throughout, holding me in its vivid portrait of Surinamese landscapes and multicultural heartbeat.

You can buy Wan Pipel via MVD Shop.

Palindromes (Todd Solondz, 2004)

I survived another Todd Solondz picture, and this one almost gave me whiplash as soon as that opening card drops. With just one line, Palindromes positions itself as a spiritual sequel to Welcome to the Dollhouse… and I had no idea how even more morally disorienting this world could get. As with much of his work, Palindromes is both deliberately alienating and morally thorny in a way that left me watching with my mouth half open, hovering between an uncomfortable smile and total horror.

Through Palindromes, we’re introduced to a 13-year-old girl named Aviva who wants to have a baby. From there, the story spirals into an escapade of ideological extremism, parental failure, and warped innocence. Although the story unfolds linearly, it’s destabilized by the fact that Aviva is played by eight different actors, all of whom vary in age, race, and even gender. Initially, I registered this as a gimmick. And yet, after I watched it unfold, it struck me: Solondz is employing a jarring device intended to universalize Aviva’s experience and challenge the audience’s unconscious biases. The result is that the viewer is never allowed to settle, never allowed to project a fixed identity onto our lead — and that’s the point.

Thanks to the Radiance Films’ release of Palindromes and the plethora of extra materials, I discovered that Solondz expressed a desire to explore the contradictions embedded in American culture, particularly the hypocrisies surrounding reproductive politics. In his words, Palindromes is about “a pro-choice mom who gives her daughter no choice and a pro-life mom who kills.” That tension forms the philosophical spine, whether we’re watching Aviva transition from a sterile suburban home to a disturbingly cheery Christian fundamentalist group (my god, does “Nobody But Jesus” haunt me now). All in all, the movie demands we sit in discomfort and reckon with the moral certainty (or uncertainty). In a visual essay on the Radiance release, Lillian Crawford posits, “Is it Solondz who is cruel, or is it the world?” You tell me.

Solondz offers perhaps his most biting thesis through Mark Weiner’s late-film monologue, where he tells Aviva that people believe they can change, but they can’t. It’s a grim kind of psychological palindrome: life looping back to sameness despite the illusion of progress. Aviva, too, becomes a kind of palindrome: not just because of her name, but because she returns from a harrowing journey seemingly unchanged in her desires. It would be easy to call this outlook pessimistic, but something in me resists. Maybe that tension is the film’s most unsettling truth: that identity is elastic, and belief is never as fixed as we think.

You can buy Palindromes via Radiance Films.

Nothing Underneath (Carlo Vanzina, 1985)

Donald Pleasence eating pasta at a Wendy’s in Milan, speaking with an Italian accent, napkin bib and all. That alone justifies a watch. But Carlo Vanzina’s Nothing Underneath is more than a late-era giallo oddity: it’s a deliciously glossy slice of ’80s murder-mystery madness that feels like a lovechild of Dario Argento and Brian De Palma. With its twin telepathy premise and tense drill scene, the film blends flourishes of the former with the latter’s voyeuristic thrills.

Set in Milan’s high-fashion world, the story follows a Wyoming park ranger (Tom Schanley) who jets off to Italy after experiencing a psychic vision of his model twin sister in danger. What follows is an enjoyably stylish whodunnit full of black-gloved killers, scissor murders (a nod to Phenomena, again!), and enough garish color and nudity to remind you this is pure giallo — and proudly so.

The fashion sequences are a standout, thanks in large part to Moschino, the only designer bold enough to sign on (according to writer Enrico Vanzina, most fashion houses feared being mocked). Complementing the visuals is a slick, moody score by Pino Donaggio, which further deepens the De Palma connection and keeps the film pulsing with tension.

There’s playful camp everywhere, from a nail-polished telephone operator spilling lacquer across a Milan area code during a moment of high urgency, to Pleasence delivering deadpan one-liners as a delightfully misplaced commissioner. The tone does occasionally wobble (particularly when it shifts from self-aware playfulness to leering sensuality), but the Rustblade release’s special features reveal that some of the more gratuitous scenes were added by the producer, who felt the film wasn’t “sexy enough.” The director and writer reportedly disagreed but let it go.

For all its tonal dissonance and occasional over-the-top performances, Nothing Underneath remains charming, confident, and wildly fun. Beneath the gloss and glam, it maintains a surprisingly solid whodunnit that satisfies the giallo faithful. "The only difference is fashion is seasonal, murder is... a year-round occurrence.”

You can buy Nothing Underneath via MVD Shop.

The Beast to Die (Tōru Murakawa, 1980)

There’s a quiet chill that hangs over Tōru Murakawa’s The Beast to Die, and it all comes from the icy void at its core. Date (Yūsaku Matsuda), a former Vietnam War photojournalist, once bore witness to death through a lens. Now, he reenacts it. What the audience is left with is the slow, bone-deep unraveling of a man, punctuated by acts of swift, eerily emotionless brutality.

Matsuda, best known for his magnetic, tough-guy screen presence (Cowboy Bebop’s Spike Spiegel was famously based on his Detective Story performance!), delivers something radically opposite here. As Date, he’s a shell: posture slumped, his gaze floating lifelessly. “What’s up with your eyes? It’s like there’s no life in them,” someone remarks, and the line lingers.

In the new Radiance Films release, screenwriter Shōichi Maruyama explains that Date’s descent began in the warzone. What he witnessed there shattered something in him. “Are humans capable of this much cruelty?” Maruyama asks. For Date, the answer is yes, and once that line is crossed, there’s no way back. The horror has reshaped him into something feral: a beast, unmoored from all conscience.

This was my first Murakawa film, and I’m already eager to explore more, especially his Game series. His visual language here is striking, toggling between slick, stylized wide-angle shots of a gritty neon world and a moodier, more haunted stillness. At times, the film flirts with Seijun Suzuki’s jazzy cool, but just as you begin to settle into the cinematic swagger, the mood drastically shifts. Suddenly, you’re in proto–Kiyoshi Kurosawa territory: hollowed-out urban dread, where everything feels nihilistic and dispassionate. Importantly, the musical tone also pivots, becoming increasingly orchestral.

It’s in those moments when Date seems most alive. In a dance between the theatrical and the detached, maybe that music mirrors Date’s very own unraveling. It builds and builds, and as the beast within devours whatever remains, the score engulfs him like a requiem.

You can buy The Beast to Die via Radiance Films.

And that’s all from me today, folks! As always, you can keep up with everything I’m watching over on Letterboxd ☻

Will be hunting down Rosa La Rose and The Beast to Die next time I’m at Barnes & noble

So many good films here that I still need to watch, I got so behind on the Radiance releases. If only they would partner with me BAHAHHA