On the Green, Off the Deep End: Seijun Suzuki’s A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness

A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness (1977) – Seijun Suzuki’s long-lost media nightmare finds new life in a lurid, satirical Radiance Films release.

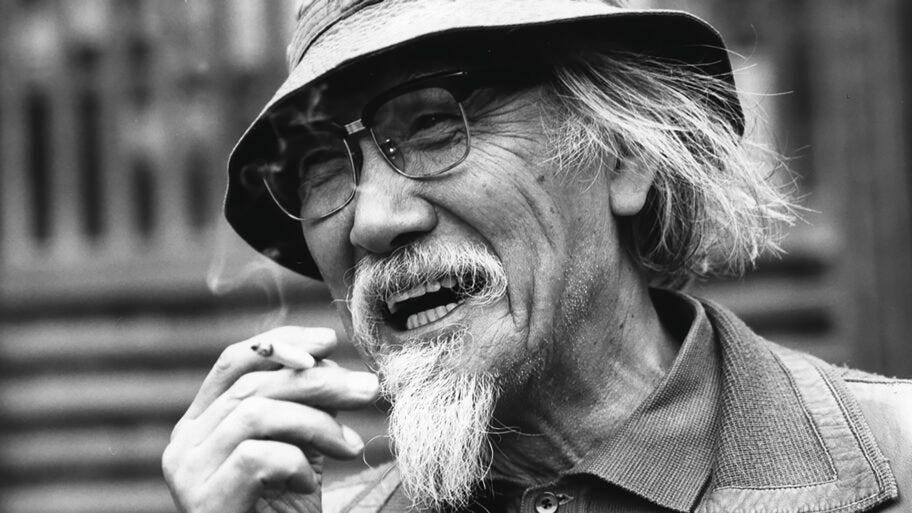

Seijun Suzuki: the so-called “maverick” director whose name has become synonymous with visual excess and rule-breaking irreverence. If you’re early in your journey with the Japanese auteur, you’ve likely encountered 1966’s Tokyo Drifter or 1967’s Branded to Kill — the latter getting him unceremoniously fired by Nikkatsu for being too “incomprehensible” (more on that later). Blacklisted for a decade, Suzuki eventually re-emerged from TV purgatory with this 1977 oddity: A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness. It’s a bold sports melodrama that begins as a story of ambition… and then mutates into something darker, stranger, and far less categorizable.

Long overlooked, the film has finally received a proper world Blu-ray premiere via Radiance Films — and it’s one I highly recommend. What makes A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness so compelling is its in-between-ness: too strange for the mainstream, too early for the arthouse. It’s a quietly radical bridge between two careers. I’m here to tell you why it deserves your attention.

Before we get into the film, let’s rewind a bit, shall we?

Seijun Suzuki entered the film industry in 1949, but not in the way you might expect. After failing the entrance exams for the University of Tokyo, he stumbled upon a film course offered by a local academy. Better yet, it was backed by major Japanese studios, offering a direct pipeline into the industry.

Ironically, Suzuki’s career began almost accidentally — more a practical move for employment than a passionate pursuit of art. And if you wanted to survive in that studio system, you had to play nice. As we’ll come to see, Suzuki did not. His time in the sandbox ended with sand thrown in his face.

After completing his course, Suzuki rose through the ranks at various film studios. He first landed at Shochiku (the same studio where Yasujiro Ozu famously worked) before being discovered by Nikkatsu, Japan’s oldest film studio. Advancement happened faster at Nikkatsu, and after apprenticing under a few industry titans, Suzuki started directing his own films. Between 1956 and 1967, he made forty films. Let’s pause on that: forty films in eleven years. Even by today’s standards, that’s a staggering pace.

It’s worth noting that the mid-1960s marked a decline in theatre attendance across Japan, which inevitably meant bad news for the studios as well. Shochiku, established in 1920, had long aimed to modernize Japanese filmmaking and move it away from theatrical traditions. Somewhat ironically, Shochiku itself began as a theatre company before pivoting to film. For a time, they thrived off familial dramas and comedies (think Ozu again) until the rise of the Japanese New Wave reshaped everything.

Unlike its French counterpart, Japan’s New Wave emerged within the studio system, notably Shochiku. The idea came from studio head Shiro Kido, who wanted to emulate the success of New Wave movements in Europe and entice younger audiences. Other studios, like Nikkatsu, followed suit. After Ozu died in 1963, Japanese cinema became more prevalent with sex and violence. Movies made in the ‘60s, such as Noboru Nakamura's The Shape of Night, Mikio Naruse’s When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, or even Suzuki’s Gate of Flesh, started to change how the masses perceived sex work and gender roles. Many filmmakers who emerged from this period eventually broke away from the system entirely, forging bolder, more confrontational paths. In doing so, they reshaped Japan’s cinematic and cultural conversation.

Curiously, though Suzuki’s work now feels emblematic of the New Wave, Nikkatsu didn’t market him as part of the movement. To me, that’s what makes him so gripping. His films were vibrant, defiant, and unconcerned with conformity; likely the very reason the studio didn’t quite know what to do with him.

It’s also worth remembering that the New Wave’s rise coincided with the arrival of television, which further contributed to declining theater numbers. As I mentioned earlier, after his dismissal from Nikkatsu, Suzuki pivoted to television for a full decade before his cinematic return. But before we go there, let’s talk about that infamous firing.

1966’s Tokyo Drifter put Suzuki on thin ice. What was supposed to be standard gangster fare morphed into its own beast, borrowing from Hollywood musicals, spaghetti westerns, film noir, and even traditional samurai tropes. The film never takes itself too seriously; it’s wrapped in glaring color and visual opulence. An exercise in style that’s hilariously self-aware. To this day, it’s my favorite Suzuki outing, and I cannot recommend it enough.

Suzuki clearly refused to conform to Nikkatsu’s standards. The result? They slashed his budget and reportedly said something to the tune of, “Bye-bye, color stock.” So what did he do? He made Branded to Kill — in black and white, no less — and delivered something just as surreal.

After one infamous screening, Suzuki got the boot. Studio head Kyusaku Hori delivered the finishing blow, declaring Suzuki’s films wakaranai — “incomprehensible.”

“Seijun Suzuki is a director who makes incomprehensible films. As such, Seijun Suzuki’s films are bad films, and to screen them publicly would be an embarrassment for Nikkatsu. Nikkatsu cannot have an image as a company that produces films that are only comprehensible to a single faction of people.”

An entire legal battle followed, which, interestingly enough, only deepened Suzuki’s cult appeal among arthouse circles and student movements. His popularity grew in time, albeit in bittersweet fashion. As he told Tom Mes in a 2001 interview:

“The best thing for a movie is to have a lot of people come to see it when it's released. But back then, my films weren't so successful. Now, thirty years later, a lot of young people come to see my films. So either my films were too early or your generation came too late. Either way, the success is coming too late."

After his dismissal, Suzuki spent the next decade in a kind of creative limbo. Still active, but essentially persona non grata in theatrical filmmaking circles, he pivoted to television: shows, made-for-TV movies, commercials, you name it. I’ve heard 1973’s A Mummy’s Love is a wonderfully eccentric TV horror — I still need to see it myself.

While I could talk about the lead-up to A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness for hours, let’s get to the main event. With all of the above in mind, this return feels even more fascinating: Suzuki’s first theatrical feature post-blacklist. It wasn’t with Nikkatsu, but with Shochiku (of all studios), adapted from a manga by Ikki Kajiwara, and its script written by Atsushi Yamatoya — who also penned Branded to Kill.

On paper, A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness sounds straightforward. It seems so straightforward, in fact, that during a local Suzuki retrospective a few years back, I actually chose to skip it. Oh, what a fool I was.

The premise sees a young woman, Reiko (Yoko Shiraki), plucked from obscurity by an advertising agency and thrust into the world of professional golf with the guidance of her manager-meets-lover, Miyake (Yoshio Harada). From there, the mounting pressure begins to suffocate her: fame, media, and the masses all eager to commodify her. Sorrow and Sadness begins like a sports film, but as we know, Suzuki was never straightforward. It opens with familiar training montages and plucky underdog tropes, until we suddenly see the lurid satire take center stage. The golf drama is merely the Trojan horse; what Suzuki delivers is a media-nightmare, fresh from the world he just spent ten years engulfed in. Playful? Yes. Angry? Absolutely.

The mutating plot of Sorrow and Sadness is slow, building with small signposts, until it becomes a direct attack on celebrity, media control, consumerism, and, to a degree, idol culture. The latter began gaining traction in the 1960s, eventually ushering in the “Golden Age of Idols” by the 1980s.

Take Reiko, who quietly complies at every turn. She’s molded into the ideal media darling: stylized, sexualized, and stripped of agency — and not just by the company signing her checks. It was never really about golf, but about how she looks wielding a 9-iron in a bikini. The image crafted around her was never her own. It was built for mass consumption. The sport becomes secondary once Reiko hits the fame threshold her “handlers” envisioned. She graduates into photo shoots, her own TV show, and relentless media training.

As the film plays out, it truly becomes a tale of sorrow and sadness. Reiko is deeply lonely; a bird in a gilded cage, engineered for appeal. Even her management-gifted home, which she shares with her younger brother, resembles a sterile showroom. Cold, barren, and bisected by a fake putting green, the space is a surreal reflection of her commodified identity.

The skewering of the media machine in the film feels personal, like it’s coming from the inside. After all, Suzuki spent a decade immersed in television work. The promotional reels we see Reiko star in made me wonder how much of that was pulled from Suzuki’s work in advertising.

Of course, the pressure cracks Reiko. While she’s grasping onto that final crumb of sanity, the women who once scoffed at her soon begin to consume her in a new way. Most disturbing is Mrs. Senbo (Kyōko Enami), a neighbour-turned-fan whose parasocial obsession twists into something more grotesque. Eventually, it’s not just Mrs. Senbo who turns on her. By the film’s fever pitch, the media has chewed Reiko up and spit her out — just another product past its prime.

While everything I’ve described so far feels undeniably harrowing, Suzuki’s trademark visual playfulness brings a surreal kind of levity. The film begins in relative visual calm (for Suzuki), but his bold use of color arrives quickly. A common complaint with his work is that these antics are just for show. Yet, as in Tokyo Drifter, Suzuki’s color choices are purposeful — if you’re willing to dig deeper. The hues start loud, then become garish. A sickly green begins to seep into Reiko’s world, first clinging to objects, then washing over faces. Her nail polish shifts throughout the film, too, perhaps mirroring a selfhood that’s constantly being repackaged. By the end, Reiko has visually dissolved into the product she was made to be.

As I mentioned, this 1977 gem serves as a bridge for Suzuki, highlighting his tenacity and mischievousness, even in the light of such a difficult career. The ensemble orbiting Reiko speaks not just to his talent, but to the thematic heft of the film. Enami, although playing the deranged Mrs. Senbo, got her start in the industry after being scouted herself by Daiei Studios in 1959. Harada, who came from a theater background but often played “tough guys” onscreen, walks that line here as Miyake, too — audiences would come to see more of him in Suzuki’s films a mere three years later, starting with Zigeunerweisen. Lastly, I’d be remiss if I didn’t highlight the cameo by Suzuki regular Jō Shishido, who briefly reminds us of the iconic crime classics they delivered together by way of Nikkatsu.

Almost half a century later, A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness feels eerily contemporary. Its themes of consumerism, parasocial obsession, and burnout speak directly to today's celebrity and influencer spaces — the industries where every glance, misstep, or breakdown becomes fodder for scrutiny. Even Reiko’s chirpy mantra, which we hear at one point, “I’m happy,” becomes haunting. The only way to soothe. After a decade spent on the periphery, yet still absorbed in the commercial fame system, Suzuki returned, letting it all go up in flames. A tale of sorrow, sadness, yes, but above all, resilience.

Gosh, I need to watch more Seijun Suzuki pronto. I still haven't seen anything besides Tokyo Drifter and that was almost two years ago.

Lol thinking about it that screening was also where we met, can't believe it's been that long already. You've introduced me to a lot of different movies in that time and really helped broadened my cinematic landscape. Thank you so much for that and for tolerating so many of my rambling thought messages about them. Hope you've been well : )